On November 21, the Government of India flipped the switch on the most significant economic reform since liberalization: the operationalization of “The 4 New Labour Codes 2025”. This is not merely a legal update; it is a fundamental restructuring of the contract between India’s employers and its 50-crore strong workforce.

For decades, the Indian labour market was governed by a tangled web of colonial-era regulations—some dating back to the 1920s—that often contradicted each other. Businesses struggled with “compliance fatigue,” navigating over 1,400 sections of law and filing hundreds of returns, while workers in the unorganized sector remained largely outside the safety net.

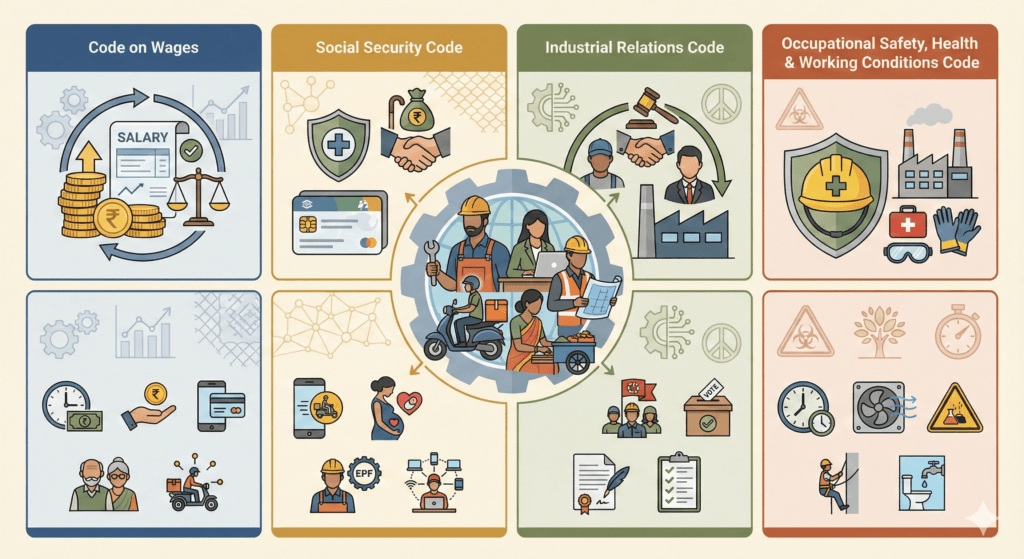

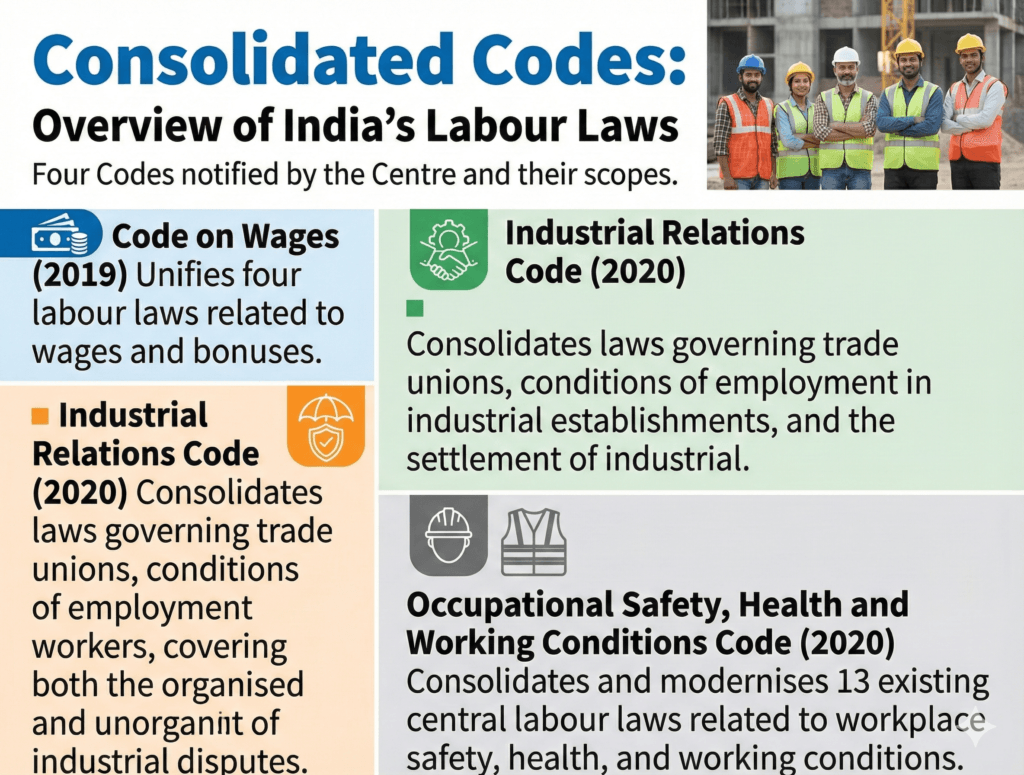

The “4 New Labour Codes 2025” framework consolidates 29 fragmented central labour laws into four unified Codes: The Code on Wages, The Industrial Relations (IR) Code, The Code on Social Security (SS), and The Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (OSH) Code. Whether you are a gig worker delivering food, a software engineer in Bengaluru, or a factory owner in Gujarat, these rules—effective immediately—change how you work, how you are paid, and how you are protected.

This detailed guide breaks down the legalese into plain English, analyzing the practical impacts, the new rights you’ve gained, and the risks that may lie ahead.

Why Were These New Labour Codes Brought In?

The rationale behind this massive codification and compilation of labour codes rests on three pillars: Simplification, Universalization, and Digitization.

1. Ending the “Inspector Raj”

Prior to 2025, a single manufacturing unit might have to maintain dozens of registers and file separate returns for the Minimum Wages Act, the Payment of Bonus Act, and the Factories Act. The definitions of “wages,” “workman,” and “employee” varied across these laws, leading to endless litigation. The New Labour Codes reduce the number of sections from over 1,200 to roughly 480 and streamline registers and returns into single digital filings.

2. Social Security for All

India’s workforce is massive, yet nearly 90% are in the unorganized sector. Previous laws largely ignored the booming “Gig Economy.” The New Labour Codes explicitly recognize “gig workers” and “platform workers” for the first time, mandating social security coverage funded by aggregators. This moves India from an employment-based protection model to a more universal social security model.

3. Adapting to Modern Realities

Old laws like the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 were framed for a factory-based economy. They did not account for “Work from Home,” “Fixed-Term Employment,” or the 24/7 service economy. The New Labour Codes legalize fixed-term employment (FTE) and allow women to work night shifts across all sectors (with consent), removing archaic restrictions that hindered workforce participation.

What Were the Previous Laws? (Summary of 29 Repealed Laws)

To understand the magnitude of this change, we must look at what has been replaced. The 4 New Labour Codes have subsumed 29 Central Labour Laws, many of which were overlapping or redundant.

| New Code | Repealed Acts (Consolidated) | Key Focus |

| Code on Wages, 2019 | Minimum Wages Act, 1948, Payment of Wages Act, 1936, Payment of Bonus Act, 1965, Equal Remuneration Act, 1976 | Regulating wage rates, bonus payments, and prohibiting gender discrimination in pay. |

| Industrial Relations Code, 2020 | Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, Trade Unions Act, 1926, Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Act, 1946 | Dispute resolution, strikes, lockouts, trade unions, and retrenchment rules. |

| Code on Social Security, 2020 | Employees’ Provident Funds & MP Act, 1952, Employees’ State Insurance Act, 1948, Maternity Benefit Act, 1961, Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972, Cine-Workers Welfare Fund Act, 1981, Building & Other Construction Workers Cess Act, 1996, Unorganized Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008, Employment Exchanges Act, 1959, Employees’ Compensation Act, 1923 | Provident Fund (PF), insurance, gratuity, maternity benefits, and compensation for injury. |

| OSH Code, 2020 | Factories Act, 1948, Contract Labour (Regulation & Abolition) Act, 1970, Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act, 1979, Mines Act, 1952, Dock Workers Act, 1986, Building & Other Construction Workers Act, 1996, Plantations Labour Act, 1951, Working Journalists Act, 1955 (Plus 5 others covering sales promotion, motor transport, beedi workers, etc.) | Health, safety standards, leave policies, and working hours. |

The Four Labour Codes: Summaries & Critical Sections

1. The Code on Wages, 2019

This Code applies to all employees/Labours in organized and unorganized sectors, ensuring a universal minimum wage and timely payment.

- The “50% Rule” (Section 2(y)): This is the most discussed change. “Wages” now include basic pay, dearness allowance (DA), and retaining allowance. The Labour Code mandates that these components must constitute at least 50% of the total remuneration. If exclusions (like HRA, conveyance, overtime) exceed 50%, the excess is added back to “Wages” for calculating social security (PF, Gratuity). This prevents employers from suppressing Basic Pay to lower their PF liability.

- National Floor Wage (Section 9): The Central Government will fix a “Floor Wage” based on minimum living standards. State governments are prohibited from setting minimum wages below this floor, reducing regional disparities.

- Overtime (Section 14): Employees working beyond normal hours (typically 8 hours/day) must be paid overtime at twice the normal rate of wages. This applies to all employees, not just factory workers.

- Settlement Period (Section 17): In case of resignation, dismissal, or retrenchment, the employer must settle all dues within two working days, a significant improvement over the previous norms which often stretched to weeks.

2. The Industrial Relations (IR) Code, 2020

This Code governs the employer-employee relationship, focusing on hiring, firing, and dispute resolution.

- Increased Thresholds (Section 77): Previously, establishments with 100 or more workers needed government permission to close down or lay off staff. This threshold has been raised to 300 workers. This grants medium-sized businesses significant flexibility but removes a layer of job security for workers/Labours in those units.

- Fixed-Term Employment (FTE) (Section 2(o)): FTE is now a fully recognized tenure. These workers are entitled to the same wages, working hours, and benefits as permanent employees. Crucially, they are eligible for gratuity after just 1 year of service, unlike the 5-year requirement for regular staff.

- Reskilling Fund (Section 83): To support retrenched workers, the Code establishes a fund where employers must contribute an amount equal to 15 days of the last drawn wages of the retrenched worker. This amount is credited directly to the worker within 45 days.

- Strike Notice (Section 62): Workers in any industrial establishment are now prohibited from striking without giving a 14-day notice. Strikes are also banned during conciliation proceedings and for 7 days after they conclude, effectively outlawing “flash strikes”.

3. The Code on Social Security (SS), 2020

This Code aims to extend the safety net to the entire workforce, including the 90% in the unorganized sector.

- Gig & Platform Workers (Sections 113, 114): For the first time, gig workers (e.g., Uber/Zomato drivers) are eligible for social security benefits like life and disability cover, health and maternity benefits, and old age protection. These schemes will be funded by contributions from aggregators, capped at 1-2% of their annual turnover or 5% of the amount paid to workers.

- Gratuity Reform (Section 53): While the general eligibility remains 5 years of continuous service, the Code explicitly lowers this to 1 year for Fixed-Term Employees, ensuring they don’t lose out on retirement benefits due to short tenures.

- Expanded ESIC Coverage: The Employees’ State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) coverage is now applicable to all establishments with 10 or more employees (voluntary for those with fewer). It is mandatory for establishments involved in hazardous work, even if they employ a single worker.

4. The OSH Code, 2020

This Code consolidates laws regarding safety, health, and working conditions.

- Single License (Section 119): Contractors and employers now need only a single license valid for 5 years, replacing the need for multiple licenses under different acts. This is a major “Ease of Doing Business” reform.

- Women in Night Shifts (Section 43): Women are now legally permitted to work in any establishment (including factories and mines) between 7 PM and 6 AM, provided the employer obtains their consent and ensures adequate safety measures. This opens up new employment avenues previously closed to women.

- Annual Health Check-up (Section 6): Employers are now mandated to provide free annual health check-ups for employees above a certain age (likely 45+, subject to state rules), promoting preventive healthcare.

- Inter-State Migrant Workers (Section 2(zf)): The definition has been expanded to include workers who migrate on their own (not just those recruited by contractors) and earn wages up to ₹18,000 per month. This ensures they can access portability benefits for the Public Distribution System (PDS) and other schemes

What Has Changed Practically for Workers and Employers?

The shift to these Labour Codes creates immediate impacts. Here is how the landscape shifts for the two main stakeholders:

For Employees (Workers)

- Take-Home Pay vs. Savings: Due to the “50% Rule” (Section 2(y) of Wage Code), if your basic salary is currently less than 50% of your total CTC, your employer must restructure it. Increasing the Basic Pay automatically increases the Provident Fund (PF) contribution (which is 12% of Basic). Result: Your monthly cash-in-hand may decrease, but your retirement corpus (PF) and Gratuity accumulation will significantly increase.

- Faster Exit Payments: If you resign or are fired, your employer must pay your full and final settlement within 2 working days. This ends the practice of holding back wages for 30-45 days post-exit.

- Better Status for Contract Workers: Fixed-Term Employees now have parity with permanent workers regarding working conditions and benefits, reducing the incentive for employers to exploit “contract” roles for permanent work.

For Employers (Businesses)

- Compliance Reduction: Instead of maintaining separate registers for Wages, Bonus, and Factories Act, businesses can maintain unified registers and file a single integrated return. This reduces administrative overheads significantly.

- Higher Financial Liability: The redefinition of wages increases the employer’s contribution to Gratuity and Leave Encashment. Companies that structured salaries with high allowances to minimize these liabilities will see their staff costs rise.

- Operational Flexibility: The increase in the closure/retrenchment threshold to 300 workers allows mid-sized factories to adjust their workforce based on market demand without bureaucratic permission, fostering a more dynamic industrial environment.

Implementation Timeline and Current Status

Effective Date: The Central Government officially notified the implementation of all four Labour Codes effective from November 21, 2025.

The “Concurrent List” Nuance: Labour is a subject in the Concurrent List of the Constitution, meaning both the Centre and States must frame rules for implementation. The Central Government frames rules for central public sector undertakings (PSUs), railways, and ports, while State Governments frame rules for private establishments within their borders.

Status as of November 2025:

- 32 States and Union Territories have pre-published their draft rules, indicating a high level of readiness.

- 18 to 25 States have already notified their final rules or are fully aligned with the Central notification.

- Laggards: Some key states like West Bengal (no draft rules published) and Tamil Nadu (yet to issue rules under the Social Security Code) are lagging. However, with the Central notification now in force, these states are under pressure to expedite their notifications to prevent a regulatory vacuum.

- Transitional Provision: Until a state notifies its specific rules, the Central Rules or the existing state provisions (where not inconsistent with the Labour Codes) generally apply, though this can create temporary ambiguity for compliance officers.

Deep Analysis: Loopholes, Risks, and Scenarios

While the New Codes are reformist, they introduce new complexities. Here are three realistic scenarios illustrating potential risks and loopholes.

Scenario 1: The “Take-Home Pay” Shock (Wage Code)

The Situation: Arjun, a marketing manager, earns a CTC of ₹12 Lakhs. His salary structure is “allowance-heavy”: Basic Pay is ₹3 Lakhs (25%), and allowances (HRA, Special Allowance, LTA) are ₹9 Lakhs (75%).

The Change: Under Section 2(y), the excluded allowances cannot exceed 50% of the total remuneration.

The Impact: Arjun’s employer must restructure his salary. His “Wage” for PF calculation is raised from ₹3 Lakhs to ₹6 Lakhs (50% of ₹12 Lakhs).

- Old PF Contribution: 12% of ₹3 Lakhs = ₹36,000/year.

- New PF Contribution: 12% of ₹6 Lakhs = ₹72,000/year.

Result: Arjun’s annual take-home pay drops by ₹36,000. While his retirement savings double, he faces an immediate liquidity crunch. Employers may also try to pass their increased share of the PF contribution cost onto the employee by reducing other variable pay components.

Scenario 2: The “300 Worker” Split (IR Code)

The Situation: A textile manufacturer employs 500 workers. Under old laws, they needed government permission to retrench staff.

The Loophole: The new threshold for permission-free retrenchment is 300 workers (Section 77).

The Impact: The manufacturer might split the business into two separate legal entities—”Unit A” with 250 workers and “Unit B” with 250 workers. Both units now fall below the 300-worker threshold.

Result: The employer gains the ability to “hire and fire” at will in both units without government oversight. This could lead to greater job insecurity for workers in what are effectively large establishments.

Scenario 3: The Gig Worker Funding Gap (SS Code)

The Situation: Zomato and Swiggy must now contribute to a Social Security Fund for their delivery partners.

The Mechanism: The contribution is capped at 1-2% of annual turnover or 5% of the amount paid to workers (Section 114).

The Risk: The math is tricky. 1-2% of turnover is a massive sum for low-margin platforms, while 5% of worker payouts is significant.

Result: Platforms will likely pass this cost to consumers. We might see a “Social Security Fee” or “Welfare Cess” added to every order. Furthermore, since gig workers often work for multiple platforms simultaneously, determining which aggregator is responsible for a specific claim (e.g., an accident while waiting for an order) remains a complex bureaucratic hurdle that the new Welfare Boards must solve.

What Should You Do Next?

For Employees:

- Audit Your Pay Slip: Check if your Basic Pay + DA is at least 50% of your Gross Earnings. If not, prepare for a restructuring.

- Activate UAN: Your Universal Account Number (UAN) is now the central key for all benefits, including the new ones for gig workers. Ensure it is linked to your Aadhaar and current bank account.

- Know Your Rights: If you are a woman working night shifts, verify that your employer is providing the mandatory transport and safety measures.

For Employers:

- Payroll Simulation: Run a simulation to identify employees falling below the 50% wage threshold. Budget for the increased employer contribution to PF and Gratuity.

- Update Contracts: Issue formal appointment letters to all employees (now mandatory under OSH Code Section 6). Update employment contracts to include the new consent clauses for overtime and night shifts.

- Review Standing Orders: If you have 300+ employees, you must certify your Standing Orders. If you have fewer, you may be exempt, but you still need clear policy documents aligned with the new Codes.

Conclusion

The implementation of the “4 Labour Codes” is a big moment for India. It replaces a “jungle” of archaic laws with a streamlined, modern framework. For the worker, it promises dignity through universal social security and timely wages. For the employer, it offers the ease of doing business through digitization and flexibility.

However, the transition will not be seamless. The coming months will see friction as payrolls are adjusted, state rules are finalized, and the new Welfare Boards for gig workers find their footing. Yet, the direction is clear: a formal, digitized, and more inclusive labour market is finally here.

🌐 Dive into more untold histories and thoughtful perspectives at thinkingthorough.com

💬 Your voice matters—let’s rediscover India’s past, together.

References

PIB Press Release: Implementation Status 2025. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=2192463

SCC Online: Overview of 4 Labour Codes. https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/11/29/india-four-labour-codes-overview-explained-scctimes/

BDO India: Key Provisions & Effective Dates. https://www.bdo.in/en-gb/insights/alerts-updates/alert-implementation-of-labour-codes-key-provisions-notified-effective-21-november-2025

Ministry of Labour: Social Security Code Highlights. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2193095

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on New Labour Codes 2025

When do the new labour codes will come into force?

The labour codes were notified for implementation starting 21 November 2025. However, their full enforcement depends on individual states issuing their respective rules.

How do the New Labour Codes affect my salary?

Wage Definition: Basic Salary plus Dearness Allowance (DA) must be at least 50% of total pay, limiting the share of other allowances.

Take-Home Pay: A higher Basic Salary increases Provident Fund (PF) and gratuity contributions. This may reduce immediate take-home pay but improves long-term benefits like retirement savings.

What are the key benefits for workers under new labour codes?

Universal Minimum Wage: A national floor wage applicable to all workers

Appointment Letters: Mandatory for every employee

Expanded Social Security: Coverage extended to gig and platform workers through aggregator contributions

Workplace Safety:

Free annual health check-ups

Clear working hour limits (maximum 48 hours per week)

Equal employment opportunities for women across all sectors