I can’t promise this article will be short — because the story of India’s independence isn’t.

It’s lengthy, layered, painful — yet deeply prestigious. It’s the story of how a land once known for its wealth and wisdom was taken over, exploited, and ultimately fought its way back to freedom.

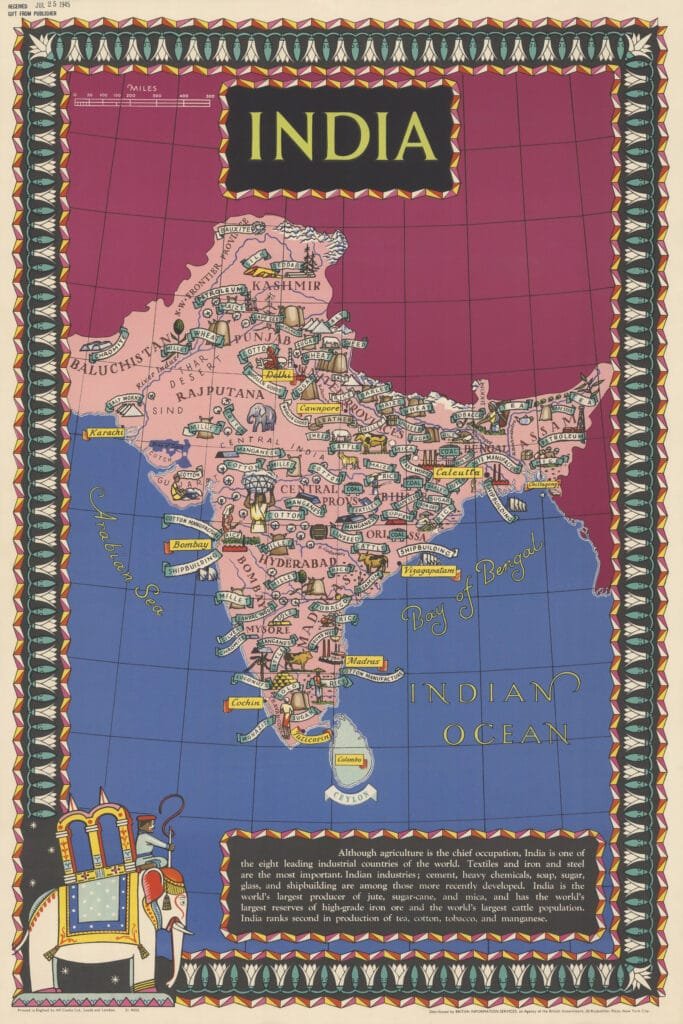

Before the British came to rule, India was a gem of the East — famous for its rich resources and booming textile trade. In the 16th century, under the Mughal Empire, India had a strong political system and welcomed foreign traders.

Among those who came were the East India Company (EIC), founded in 1600 under Queen Elizabeth I. Originally set up to trade in spices in Southeast Asia, the Company soon struggled — Dutch rivals were strong, and English wool had no market in the tropical climate. So, it looked toward India.

At first, it was a simple business decision. India’s textile industry was profitable, and by the early 1700s, the EIC was earning millions of pounds trading Indian goods. It set up trading posts in Surat, Madras, Bombay, Calcutta, and more — becoming a powerful economic force.

But this was no ordinary company. Thanks to its royal charter, the EIC had its own army. Initially used for protection, this force became a tool of expansion. And when the Mughal Empire weakened after Emperor Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the Company seized the chance.

What began as trade soon turned into territorial control. Armed, wealthy, and politically cunning, the East India Company transformed from a trader to a ruler. And with that, India’s long, complex struggle for freedom had begun.

The Rise and Rule of the East India Company (1600–1857)

From Traders to Rulers

The East India Company didn’t land in India with dreams of ruling it. Like many other European powers, it came for trade—spices, textiles, and riches. But fate had other plans.

After Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb died in 1707, the once-mighty Mughal Empire began to collapse. India became a patchwork of weak regional powers. Sensing an opportunity, the British slowly stepped in.

A major turning point came in 1757 at the Battle of Plassey, where a young Robert Clive led Company forces to defeat the Nawab of Bengal. Just a few years later, after the Battle of Buxar in 1764, the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II handed the Company dewani rights—the authority to collect taxes in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. A trading company had become a ruling power.

Expansion and Control

With power came scrutiny. The British Parliament, alarmed by the Company’s corruption and unchecked authority, stepped in:

- Regulating Act of 1773: Made Warren Hastings the first Governor-General and set up a Supreme Court in Calcutta.

- Pitt’s India Act of 1784: Split control between the Company (trade) and a British-appointed Board (politics). Indian territories were now officially “British possessions.”

But the British didn’t always use war to expand. Clever policies did the job just as well:

- Subsidiary Alliance: Indian rulers had to host British troops (at their own cost) and give up foreign diplomacy. The Nizam of Hyderabad was the first to accept in 1798.

- Doctrine of Lapse: Enforced by Lord Dalhousie, this policy annexed kingdoms without a male heir—ignoring the Indian tradition of adoption. Even powerful states like Jhansi and Nagpur were taken.

The annexation of Awadh in 1856, justified as a case of “misrule,” felt especially bitter to Indians. These takeovers made the Company richer but fueled growing resentment.

Behind the Wealth: Exploitation and Famine

While the British built an empire, Indians bore the brunt. Farmers were taxed heavily—no matter if crops failed or famine loomed. During the Bengal Famine of 1769–70, 1 to 4 million people died, while the Company looked away.

Local industries, especially textiles, collapsed under the weight of cheap British imports. Skilled weavers lost their jobs. A proud tradition of craftsmanship was destroyed.

Cultural Interference or Reform?

The British introduced English education and passed reforms like banning Sati (1829) and allowing widow remarriage (1856). While some saw these as progressive, others viewed them as cultural intrusion.

Missionary activities and forced conversions worsened mistrust. For many Indians, it felt like their religion, traditions, and identity were under threat.

The final straw was the infamous greased cartridge issue—where sepoys were ordered to bite cartridges greased with cow and pig fat, offending both Hindus and Muslims. This small act lit a spark across the army.

Disrespect and Discontent

The British stripped away symbols of India’s pride—removing Mughal names from coins and evicting Bahadur Shah Zafar’s family from the Red Fort. Indian soldiers faced discrimination in pay and harsh treatment, while even being forced into overseas service, which many believed defiled their faith.

It all added up—economic ruin, cultural assault, political betrayal, and daily humiliation.

By the mid-1800s, discontent was boiling across India. And in 1857, it would erupt in rebellion.

The Great Rebellion of 1857: A Catalyst for Change

The Revolt of 1857, often called the Sepoy Mutiny or the First War of Indian Independence, wasn’t just an angry outburst by soldiers—it was the eruption of deep-rooted frustration against British rule. Indian sepoys in the British army suffered from discrimination, poor conditions, and unequal pay. The final spark came when the new Enfield rifle cartridges, rumored to be greased with cow and pig fat, offended both Hindu and Muslim sentiments. When 85 sepoys in Meerut refused to use them, they were punished—and on May 10, 1857, the rebellion exploded.

But the discontent ran far deeper. The British policy under Lord Dalhousie’s Doctrine of Lapse allowed them to annex kingdoms with no male heir or those deemed misgoverned. This enraged rulers like Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, who rose as a symbol of fierce resistance. The annexation of Awadh further alienated nobles, soldiers, and the common people. Economically, India bled under British policies. Harsh systems like Permanent Settlement, Ryotwari, and Mahalwari pushed farmers into debt and despair, while local industries collapsed under the weight of cheap British imports—leaving artisans and millions jobless.

The British also meddled with Indian religious and cultural life. Reforms like the ban on Sati (1829) and legalisation of widow remarriage (1856), though progressive in principle, were viewed by many as interference. Missionary activity and fears of forced conversion only deepened suspicions that British rule threatened India’s religious and cultural identity.

So, the rebellion wasn’t just military—it was a people’s revolt. Sepoys, princes, farmers, artisans, Hindus, and Muslims united in outrage. It was a shared resistance against political betrayal, economic exploitation, and cultural intrusion.

Although the British ultimately crushed the uprising, the consequences were far-reaching. The East India Company was dissolved in 1858, and India came under direct control of the British Crown, marking the beginning of the British Raj. A Viceroy replaced the Governor-General, and a Secretary of State for India in London now controlled policy through a council. The British abandoned aggressive expansionist tactics—the Doctrine of Lapse was dropped, and princely states were retained as allies under indirect rule. They also became cautious about interfering in religious customs, attempting to portray a more “respectful” governance model.

But the most significant legacy was psychological. The revolt, though unsuccessful, lit the first flame of nationalism. For the first time, Indians realised they had a shared struggle that cut across caste, religion, and region. It planted the seeds of a freedom movement, reminding a colonised nation that even the mighty British Empire had its vulnerabilities—and that freedom was not a distant dream.

The British Raj and the Rise of Nationalism (1858–1919)

After the Revolt of 1857, the British Crown took direct control of India from the East India Company. This marked the start of the British Raj — a period of tighter British rule. But alongside this firm grip, something powerful was brewing among Indians: a growing sense of nationalism.

How the British Reshaped Indian Governance

With the Crown now in charge, the British introduced a series of laws to govern India more centrally — but always in a way that kept real power in their own hands:

- 1858: The Government of India Act ended Company rule. India would now be governed by the British monarch through a Viceroy in India and a Secretary of State in London. This created a system where decisions about India were made from across the seas.

- 1861: The Indian Councils Act allowed a few Indians (nominated, not elected) to join the law-making councils. A small gesture, mostly symbolic — but it was the first official involvement of Indians in legislation.

- 1892: More members were added to councils, and some Indians could now be indirectly chosen. They could discuss the budget — but not vote on it. It was participation with limits.

- 1909: The Morley-Minto Reforms introduced separate electorates for Muslims, meaning Hindus and Muslims would now vote separately. This was a turning point. Though more Indians entered the councils, the move divided communities politically.

- 1919: The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms brought a system called Dyarchy in provinces — Indians got to handle subjects like education and health, while the British kept control over police and finance. Two legislative houses were also introduced at the center.

These reforms looked progressive on paper, but the British cleverly kept the upper hand. They introduced change slowly, only when pressured by growing Indian demands, and made sure British members always outnumbered Indian ones in key decisions.

Seeds of Division

The idea of separate electorates, introduced in 1909, sowed the seeds of division. It made people think of their political identity in terms of religion. Hindus and Muslims, once united in their opposition to British rule, started drifting apart politically.

By telling each community to vote separately, the British sent a dangerous message: “You are different.” Over time, this led to the belief that Hindus and Muslims were not just different groups, but different nations. This belief would later become the Two-Nation Theory, and eventually shape the painful story of Partition.

| Law | Year | Impact |

| Govt. of India Act | 1858 | Ended Company rule; Viceroy appointed; India ruled from Britain |

| Indian Councils Act | 1861 | Nominated Indians allowed in council; first token representation |

| Indian Councils Act | 1892 | Some Indians indirectly chosen; could discuss, not vote |

| Morley-Minto Reforms | 1909 | More Indian members; separate electorates introduced |

| Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms | 1919 | Dyarchy in provinces; two-house legislature; communal representation widened |

| Government of India Act | 1935 | Provincial autonomy; Dyarchy at center; Federal Court & RBI established |

The Rise of Political Awakening

While the British tightened control, Indians began organizing:

- Indian National Congress (INC) was formed in 1885, mainly by English-educated Indians. In its early years, it believed in constitutional methods — petitions, resolutions, and peaceful dialogue with the British.

- All-India Muslim League (AIML) came up in 1906, initially to protect Muslim interests. It strongly supported separate electorates, which it helped secure in 1909.

This gave rise to two visions for India:

- A united country under the INC.

- A separate Muslim identity under the League.

The Two-Nation Theory, first voiced by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and later advanced by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, argued that Hindus and Muslims were not just different faiths, but different nations with distinct cultures, laws, and lifestyles. This became the ideological base for the demand for Pakistan.

In hindsight, British policies like communal electorates were not just political strategies — they left behind deep scars. Whether by design or default, Divide and Rule became one of the most enduring legacies of the Raj.

From Protest to Resistance: India’s Final Push for Freedom (1920–1947)

This was the era when India’s freedom struggle truly became a people’s movement — no longer confined to petitions or elite leadership. It was now powered by masses — farmers, workers, women, and students — led by a man whose weapon was peace: Mahatma Gandhi.

Gandhi returned to India in 1915 after leading civil rights struggles in South Africa. By 1921, he had emerged as the face of India’s freedom movement. But his vision was broader than political independence. Gandhi fought poverty, untouchability, gender inequality, and aimed to bring communal harmony across religions and castes — using the force of Satyagraha (truth-force), or nonviolent resistance.

The first major wave came with the Non-Cooperation Movement (1920–22), launched in response to the horrific Jallianwala Bagh massacre and increasing British repression. Gandhi urged Indians to boycott British institutions — schools, courts, titles, jobs, foreign clothes. People embraced khadi, left government posts, and protested liquor shops. Though largely peaceful, the movement came to a sudden halt after a violent episode in Chauri Chaura where protestors killed police officers — a moment that pained Gandhi deeply and led him to suspend the campaign.

But the fire was lit. Ordinary Indians had begun to believe that freedom wasn’t a distant dream — it could be achieved.

The second wave came with the Civil Disobedience Movement (1930–34). Gandhi now asked people to openly break British laws. It began with the famous Dandi March — a 240-kilometre walk to the sea where Gandhi made salt, defying British monopoly. From peasants to zamindars, Indians stopped paying taxes, boycotted British goods, and courted arrest in mass protests. The salt became a symbol — simple yet revolutionary — and India’s demand for freedom grabbed global attention.

Then came the most uncompromising cry yet — “Quit India!”

With World War II in full swing, Gandhi and the Congress launched the Quit India Movement in 1942. His words — “Do or Die” — echoed across the country. The British arrested Gandhi and top leaders almost immediately, but protests exploded nationwide. Students, workers, women, villagers — all joined in. Railways were sabotaged, post offices shut down, and civil authority was challenged like never before.

The British responded with brute force. Thousands were jailed, beaten, or killed. But the message was clear: India would not wait anymore. The world was watching. And after the war, Britain knew the empire could not hold India any longer.

Gandhi’s nonviolence wasn’t just a political strategy — it was a moral revolution. It exposed the hypocrisy of British rule and built India’s resistance on ethics rather than arms. It inspired global leaders and showed that a mighty empire could be challenged with truth, unity, and discipline.

But Gandhi wasn’t alone.

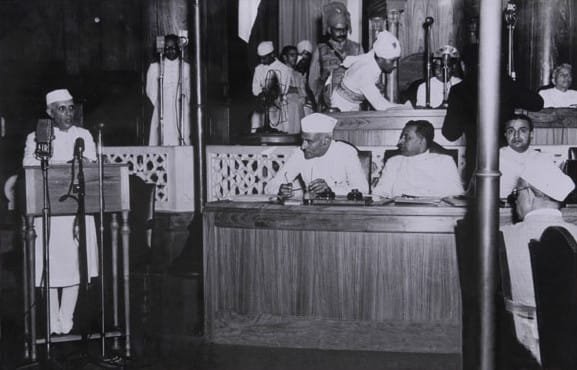

Jawaharlal Nehru, his close ally, brought passion and vision. After joining the movement in 1912 and witnessing the 1919 Amritsar massacre, Nehru became a leading voice. He demanded complete independence, led Congress as its president in 1929, endured nine imprisonments, and after independence, became India’s first Prime Minister. He championed modern education, secularism, science, and global neutrality through his policy of non-alignment.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the “Iron Man of India,” worked behind the scenes to unify India after 1947. Over 500 princely states had to be brought into the fold. Patel used tact, diplomacy, and firmness — offering privy purses to some, but using police force where needed, like in Hyderabad and Junagadh. His efforts shaped the political map of India as we know it today.

Then there was Subhas Chandra Bose, known as Netaji. A fiery patriot, he didn’t believe in Gandhi’s path of nonviolence. He believed in direct action and saw World War II as a chance to strike. With Japanese support, he raised the Indian National Army (INA) and launched military campaigns against the British. Though the INA didn’t succeed militarily, Bose’s actions electrified the nation. His call — “Give me blood, and I shall give you freedom” — stirred fierce nationalist pride. He dreamt of a secular, socialist India, free from caste and communal divides.

Between Gandhi’s peaceful resistance and Bose’s militant defiance, between Nehru’s democratic ideals and Patel’s political pragmatism — India’s freedom struggle became a chorus of courage.

And by the end of World War II, the British finally realised: they were no longer ruling a colony — they were facing a nation awake.

Major Events That Pushed India Towards Freedom

India’s road to independence wasn’t a single movement or a one-time protest—it was a series of powerful events that shook British rule, united Indians from different walks of life, and made it impossible for the British to stay any longer.

It all began with the Simon Commission in 1927. Sent by the British to review how the Government of India Act (1919) was working, it had no Indian members—only British ones. This deeply insulted Indians. Protests erupted across the country. In Lahore, freedom fighter Lala Lajpat Rai was injured by police during a peaceful march and later died. The cry of “Simon Go Back!” echoed across India, bringing people together and building momentum that would later explode into the Civil Disobedience Movement.

Then came World War II (1939–1945). Britain was heavily damaged—its economy was nearly bankrupt, and its grip over colonies weakened, especially after its failure to defend against Japan. The war also gave Indians more confidence. Thousands who had served in the British army returned home with a stronger sense of national pride. The Quit India Movement gained massive support during this time. The Atlantic Charter—signed by Britain and the U.S.—spoke of people’s right to self-rule, which only added to the pressure. Britain was looking weaker than ever.

After the war, came another emotional moment—the INA Trials of 1945. The British decided to try leaders of the Indian National Army (INA), formed under Subhas Chandra Bose, who had fought alongside Japan. But instead of dividing people, the trials united them. Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs—all rallied behind the INA soldiers.

Inspired by this, in 1946, over 10,000 sailors of the Royal Indian Navy rose in revolt. They were protesting poor conditions, racism, and colonial rule. Even though the British crushed the mutiny, it became clear that they could no longer count on Indian soldiers to keep the empire running. This shook their confidence in controlling India.

In the same year, the Cabinet Mission arrived from Britain, led by Prime Minister Clement Attlee, to find a peaceful way to transfer power. The plan suggested a united India with a federal structure—grouping provinces into clusters and giving them autonomy. It rejected the idea of Pakistan and suggested forming a Constituent Assembly to draft the Constitution, along with an Interim Government.

At first, both Congress and the Muslim League agreed. But disagreements followed, especially over the issue of Pakistan. The League pulled out and called for Direct Action Day on August 16, 1946—a day that turned into horrific communal violence in Calcutta and elsewhere, killing thousands. It was clear then: the growing Hindu-Muslim divide was making a united India nearly impossible.

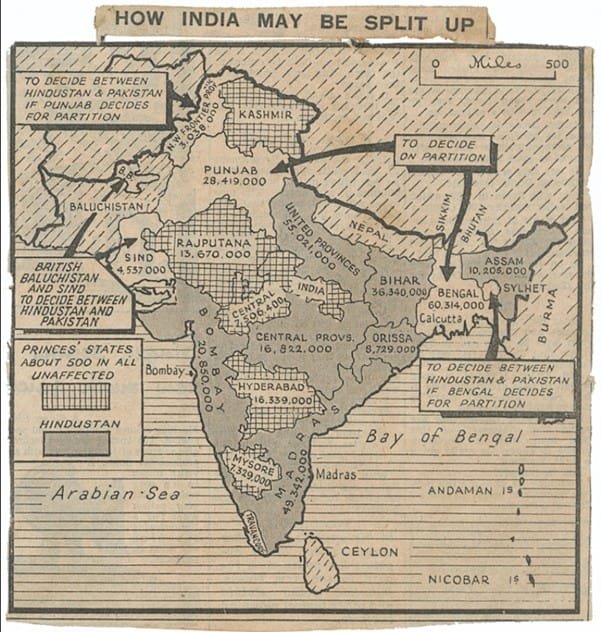

As tensions spiraled, Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, stepped in. He proposed a partition of India into two countries—India and Pakistan. Provinces like Punjab and Bengal would be split along religious lines. In some areas, people voted in referendums to decide which country to join.

To stop further violence and cut short British responsibility, the date for independence was moved up. The Indian Independence Act was passed in July 1947, and India finally became free on August 15, 1947.

Independence and Partition (1947)

At midnight on August 14–15, 1947, India and Pakistan were born, ending nearly 200 years of British rule. But freedom came with a heavy price—the trauma of Partition.

Why Partition?

- The Two-Nation Theory, promoted by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, said Hindus and Muslims were two separate nations and needed their own homelands.

- The Cabinet Mission had tried to keep India united, but the communal riots, especially after Direct Action Day, made the British and Indian leaders think that division was the only way to avoid civil war.

- The Mountbatten Plan was meant to calm tensions quickly and allow a smooth transfer of power.

The Aftermath

- 10 to 18 million people crossed new borders in a desperate and chaotic migration.

- Between 500,000 to 2 million people were killed in the violence that followed.

- Families were split, homes were lost, and communities were shattered.

- Partition also triggered long-term conflicts, especially in Kashmir, which still causes tensions between India and Pakistan.

Why Did the British Really Leave India?

Britain’s departure from India in 1947 wasn’t the result of one big event, but a combination of economic exhaustion, growing resistance, international pressure, and strategic retreat. After World War II, Britain was financially broken. The war had drained its economy, forcing it to rely on U.S. loans and ration basic necessities at home. Managing a massive colony like India had become far too expensive. With fuel shortages, freezing winters, and a collapsing economy, continuing imperial control simply became unmanageable.

At the same time, Indian resistance had reached a tipping point. Movements like Quit India showed the sheer will of the Indian public to break free, and the INA trials along with the Royal Indian Navy mutiny proved that even the military — once a stronghold of British rule — could no longer be trusted. To suppress the growing unrest would have required massive reinforcements, money, and public support — none of which Britain had.

Globally, the winds were changing. The world had begun rejecting colonialism as outdated and immoral. With the Atlantic Charter promoting the right to self-governance and the rise of global anti-colonial sentiment, Britain was increasingly isolated in holding on to its empire. Allies like the United States also quietly pressured Britain to decolonize, especially as democratic values came to the forefront post-war.

Some believe the British exit was not entirely forced, but partially staged. There’s an argument that they felt their “civilizing mission” was complete — having introduced education, law, and governance. The Labour government under Clement Attlee genuinely supported Indian independence, but also saw an opportunity to maintain soft power. By offering Dominion Status, they could let India and Pakistan go, while keeping them within the British Commonwealth — a clever way to step back without completely cutting ties.

In truth, it was a mix of all these reasons — fear of revolt, economic desperation, and political calculation — that finally convinced Britain to walk away from one of the brightest jewels in its crown.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Independence

India’s independence in 1947 wasn’t just a political event — it was the result of centuries of exploitation, people’s resistance, and the rise of a powerful freedom movement.

It began with the East India Company, which came to trade but soon took over land and power through tactics like the Subsidiary Alliance and Doctrine of Lapse. As the Mughal Empire declined, the British expanded control — draining resources, ruining industries, and interfering in India’s social fabric. The suffering fueled anger.

The Revolt of 1857 was the first major rebellion. Though it failed, it led to direct rule by the British Crown. Limited reforms followed, but real power remained with the British.

In the 20th century, organized nationalism emerged. The Congress demanded self-rule, while the Muslim League pushed for a separate Muslim state. Policies like separate electorates deepened communal divides.

Under Mahatma Gandhi, the movement gained mass momentum — through non-violent protests like the Non-Cooperation, Civil Disobedience, and Quit India movements. These united Indians across regions, castes, and religions. Meanwhile, World War II weakened Britain. The INA trials and Naval Mutiny revealed unrest in even the military. Britain couldn’t hold on — the cost was too high, support too low, and the world too critical of imperialism.

But freedom came at a price. The rushed Mountbatten Plan led to Partition, with horrific violence and mass displacement. India and Pakistan were born in trauma, not celebration.

The British didn’t leave out of kindness — they left because they had no choice. Their empire was collapsing, and they exited quickly to avoid responsibility for the damage left behind. India’s independence wasn’t just a victory over colonialism — it was a story of courage, sacrifice, and painful rebirth. One that continues to shape the subcontinent even today.

🇮🇳 Share this story to honour India’s journey to freedom.

🌐 Dive into more untold histories and thoughtful perspectives at thinkingthorough.com

💬 Your voice matters—let’s rediscover India’s past, together.

References

Admin. (2024, January 29). Regulating Act 1773 – Background, Provisions & Drawbacks [NCERT Notes: Modern Indian History For UPSC]. BYJUS. https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/ncert-notes-regulating-act-1773/#:~:text=The%20Regulating%20Act%20of%201773%20(formally%2C%20the%20East%20India%20Company,and%20centralised%20administration%20in%20India.

British rule in India: Establishment & Rule of British Crown – UPSC notes. (n.d.). Testbook. https://testbook.com/ias-preparation/british-rule-in-india

Kulik, & M, R. (2024, March 18). Quit India Movement | History, Gandhi, Congress Party, & Indian Independence. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Quit-India-Movement

Teekah, & Ethan. (2025, July 28). Indian Independence Movement | History, Summary, timeline, Causes, & facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Indian-Independence-Movement

What was the East India Company? (n.d.). National Trust. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/discover/history/what-was-the-east-india-company

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, July 22). Indian independence movement. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_independence_movement

Image 1 Credit : By Ministry of Defence (GODL-India), GODL-India, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71612901

Image 2 Credit : By British Information Services, an agency of the British Government, restoration by Wilfredor – File:India, by British Information Services, 1944.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=159639613

Image 3 credit : The National Archives, UK – “Map of possible partition of India, 1947”

Source: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

Image 4 Credit : By Unknown author – http://m.indianexpress.com/photos/picture-gallery-others/independence-day-pictures-from-1947-you-must-see/2140299/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35157349