Before 2012, India had no dedicated national law against child sexual abuse. Child victims had to rely on general IPC provisions (like Section 375 on rape or Section 354 on molestation). These laws had major gaps: for example, IPC 375 covered only vaginal rape of females (so it did not protect boys or non-vaginal assaults). Section 354 (“outraging modesty”) applied only to women and was vaguely defined; Section 377 (“unnatural offences”) punished only limited acts.

A notorious 1966 case (State of Punjab v. Major Singh) even acquitted a man who had raped an infant, reasoning that a 7½ month old “does not possess … modesty”. Such absurd outcomes highlighted the need for a child-specific law. Law Commission reports (1971, 2000) had recommended special legislation for child abuse, and surveys confirmed the urgency – a 2007 study found over 50% of Indian children (both girls and boys) reported experiencing sexual abuse by age 18.

In response, Parliament enacted the POCSO Act, 2012, which came into force on 14 November 2012. Its preamble makes clear the goal: to protect children from “sexual assault, sexual harassment and pornography” and to ensure a child-friendly judicial process. POCSO therefore fills the gaps of IPC by creating new offences and procedures focused solely on children’s safety.

Key Provisions of the POCSO Act

Under POCSO, a child is anyone under 18 years of age. The Act is gender neutral – it covers both girls and boys as victims (and applies to offenders of any gender). Major offences include (definitions paraphrased for clarity):

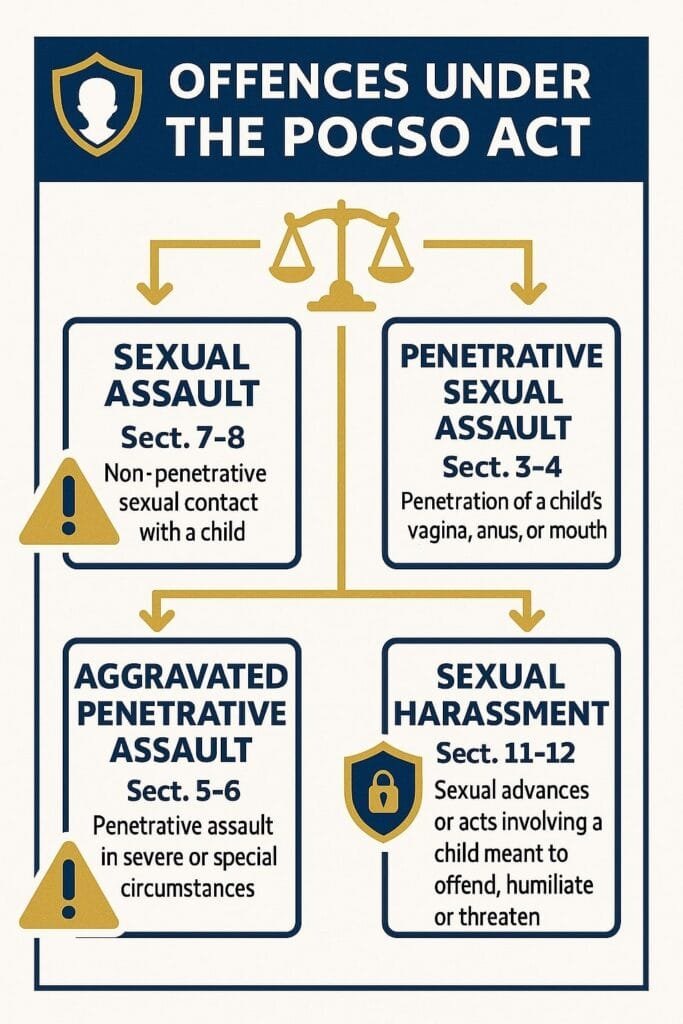

- Penetrative Sexual Assault (Sec 3): Any non-consensual penetration of a child’s vagina, anus or mouth by a penis, object, finger or any body part (or causing the child to do so).

- Aggravated Penetrative Assault (Sec 5): As above, but aggravated if the offender is in a position of trust or authority over the child (e.g. a parent, guardian, teacher, doctor, police officer) or if the child has a disability.

- Sexual Assault (Sec 7): Any intentional sexual touching of a child’s body (other than penetration), such as fondling a child’s breasts, buttocks or genitals.

- Aggravated Sexual Assault (Sec 9): Sexual assault with the same aggravating factors (trust/authority or child’s vulnerability) as in Sec 5.

- Sexual Harassment (Sec 11): Showing pornography to a child, making sexual comments or gestures, stalking a child, disrobing/attempting to disrobe a child, or other acts meant to shame or harass the child sexually.

- Use of Child for Pornography (Sec 13): Involving or depicting a child in any pornographic activity. Sections 14–15 also cover child pornography content: anyone who produces, distributes, or possesses pornographic images/videos of a child is punishable (including simply storing/viewing them).

All POCSO offences are strict liability: a child’s consent is legally irrelevant. In fact, Sec 29 bars any cross-examination about the child’s sexual history, and Sec 30 creates a presumption that if the prosecution proves the victim was under 18 and a sexual offence occurred, the accused is presumed to have had sexual intent and knowledge of the child’s age. In practice, once the basic facts are established, the accused must prove lack of intent.

Punishments under POCSO are severe. For example:

- Penetrative assault (Sec 3): minimum of 10 years’ rigorous imprisonment

- Aggravated penetrative assault (Sec 5): 20 years to life, and the 2019 amendment added that the death penalty may be imposed for “rarest of rare” aggravated cases

- Other punishments include:

- Sexual assault (Sec 7) – 3–5 years

- Aggravated sexual assault (Sec 9) – 7–10 years

- Sexual harassment (Sec 11) – 1–3 years

- Using a child in pornography (Sec 13) – 5–7 years

- Possessing child pornography (Sec 15) – up to 3 years

(All terms include fines as well.)

Importantly, Sec 33(8) allows the Special Court to order compensation to the child for physical or psychological trauma. In other words, the court can direct the offender to pay the victim’s medical or counselling expenses in addition to punishing him. This makes POCSO a uniquely victim-centric law.

Child-Friendly Procedures and Special Courts

The POCSO Act mandates a specially tailored justice process to minimize further trauma to the child. Section 28 requires each state to notify Special Courts (Sessions Courts) for POCSO offences in every district. These courts have the powers of a Sessions Judge and give priority to POCSO cases. The law directs that the child’s testimony be recorded quickly (within 30 days of trial beginning) and that the trial concludes as far as possible within one year, which is much faster than ordinary trials.

Recording of evidence must be child-friendly. Under Section 24 read with CrPC 164-A, the child’s statement is to be recorded by a female officer or a magistrate of the child’s preferred gender. The law also states that the officer should not wear a uniform, to avoid intimidating the child. Section 26(3) explicitly forbids confronting the child with the accused during testimony, and Section 26(4) prohibits detaining the child at a police station overnight.

Courts have consistently held that a child’s testimony should be taken at the earliest possible time and in a stress-free environment. The Act also allows the use of video conferencing or screens so the child need not directly face the accused. (Section 26(2) even permits recording the testimony via video link if the child is in another location.)

All POCSO trials are conducted in-camera, i.e., privately. Only the judge, the child, parents/guardians, and necessary court personnel may be present. The media is strictly barred from identifying the child. Section 23 prohibits publishing the child’s name, address, photos, school, or any detail that could reveal identity. Violating these confidentiality rules can lead to 6 months to 1 year imprisonment and fines. The Preamble of the Act emphasizes that the child’s best interests and dignity must be protected at all stages.

Another important provision is mandatory reporting. Section 19 makes it compulsory for any person (doctor, teacher, neighbor, family member, etc.) with knowledge of a child sexual offence to report it to the police or Child Welfare Committee. Failure to report (as per Section 21) is punishable by up to 6 months’ imprisonment. This effectively removes any legal excuse for silence or cover-up. Additionally, the law ensures legal support for the child: courts can appoint a lawyer or expert to assist an unrepresented child under Section 39, and the government must cover legal aid for the child if needed under Section 40.

Amendments to the POCSO Act

The POCSO Act has undergone several amendments over the years to stay aligned with the evolving nature of sexual offences, especially those facilitated through technology. Among these, the 2019 Amendment Act stands out as particularly significant, as it introduced tougher penalties and broader definitions to plug existing legal gaps.

One of the most important changes was the enhancement of punishments for major offences. For example, the minimum sentence for penetrative sexual assault was raised from 7 years to 10 years, which may extend to life imprisonment. In cases of aggravated penetrative sexual assault—such as when committed by a police officer, a person in authority, or during communal violence—the minimum punishment was increased to 20 years, which can also extend to life. Additionally, the amendment introduced the death penalty in the “rarest of rare” cases involving the most heinous forms of aggravated penetrative assault, particularly where the child victim is under 12 years of age.

The 2019 amendments also took a significant step forward in tackling cyber-enabled sexual crimes, particularly child pornography and online sexual exploitation. For the first time, the law explicitly defined the term “child pornography”, distinguishing it from general pornography. Sections 13 to 15 of the Act were strengthened to criminalize not just the creation and transmission, but even the storage or possession of pornographic material involving children. This means that even downloading, sharing, or failing to report such material now qualifies as a punishable offence under the law.

To facilitate effective prosecution of cyber offences involving children, Section 28(3) was inserted. It empowers Special POCSO Courts to also try offences punishable under Section 67B of the Information Technology Act, 2000, which deals with publishing or transmitting material depicting children in sexually explicit acts in electronic form. This provision also covers acts like online grooming, luring, or blackmailing children, making it easier for courts to address such complex crimes under one umbrella.

Another essential update relates to cases where the accused themselves may be minors. As per Section 34, if the accused is found to be below the age of 18, the case must be dealt with under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, ensuring a rehabilitative rather than punitive approach. However, if there’s any ambiguity about the accused’s age, the Special Court is required to make a determination based on documentary or medical evidence. This ensures procedural fairness, while maintaining the legal distinction between child victims and child offenders.

In essence, the 2019 amendments greatly enhanced the scope and strength of the POCSO Act. By introducing harsher punishments, acknowledging new-age digital crimes, and aligning with other child protection frameworks, these changes mark a progressive step forward in securing a safer environment for children both in the real and virtual world.

Landmark Judgments and Legal Interpretations

Courts have consistently interpreted POCSO to provide broad protection to children. A key case is Jarnail Singh v. State of Haryana (2013). Although decided under the older rape laws, its reasoning carries over. The Supreme Court held that documentary proof—such as birth certificates, school records, and exam certificates—is the primary method to prove a victim’s age, with bone ossification tests as a last resort. Crucially, it ruled that any “consent” by a minor is irrelevant—a minor cannot legally consent to sexual activity. This principle is foundational in POCSO cases.

In Attorney General for India v. Satish (2021), the Supreme Court overturned a controversial Bombay High Court decision that had required a “skin-to-skin” contact for conviction. The High Court had acquitted an accused because the child’s clothes acted as a barrier. The Supreme Court emphatically rejected this interpretation, stating that POCSO aims to protect children from all forms of sexual abuse, and that intention, not technicalities like clothing, is key. The Court held that touching a child through clothes or any act fulfilling offence elements is punishable under the Act. This case reinforced a liberal and child-centric interpretation of POCSO.

A significant 2024 case—Just Rights for Children’s Alliance v. S. Harish—clarified Section 15 on child pornography. The Supreme Court ruled that possessing or viewing child pornographic content is an offence, unless the accused can prove immediate deletion and police notification. Justice Pardiwala observed that even downloading such content demonstrates sexual intent, making it punishable. The Court emphasized the broad language of the provision and placed a strong burden of proof on the accused once possession is shown.

Several High Courts have tackled related issues. Nearly all reject a marital rape exemption under POCSO: for instance, the Kerala High Court held that intercourse with a minor wife falls under the Act because there is no marriage-based exception. On teen consensual relationships, courts are divided. Some have acquitted when both are minors within a close age range, citing Section 42(1), while others treat such acts as offences, especially where there is penetration or coercion. The overall trend is toward a strict and protective interpretation in favour of the child.

Challenges and Debates

Despite its robust framework, POCSO faces serious implementation challenges. Many cases remain unreported due to social stigma, fear, or lack of awareness. Even when reported, several issues persist—many police stations lack trained child protection officers, child-friendly interview rooms, or proper adherence to child-sensitive procedures. Special Courts and child psychologists are in short supply in various regions. Consequently, delays in trial and low conviction rates are common—some reports show conviction rates below 10%.

Another debate revolves around POCSO’s strict age of consent rule—any sexual activity involving someone under 18 is criminal. Critics argue this may criminalize consensual teenage relationships. In 2025, the NGO Enfold questioned whether a relationship between a 17-year-old and a 16-year-old should be exempt. The Law Commission of India (2023), after reviewing such concerns, recommended not lowering the age of consent, fearing it may create loopholes for exploitation. Instead, it proposed limited judicial discretion in “borderline cases”, where both parties are older teenagers, while maintaining 18 as the standard.

This debate remains ongoing, but most legal experts caution that any change must not dilute child safety.

Ultimately, POCSO was never meant to criminalize teenage romance; its core aim is to protect minors from abuse and exploitation. As legal scholars point out, the Act includes “child-friendly mechanisms” throughout—from complaint filing to trial—and mandates that the child’s best interest always be the guiding principle. For policymakers and practitioners, the primary focus remains on better implementation: speedy trials, victim counselling, and strong deterrence—rather than diluting protective provisions.

Conclusion

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012 is more than just a statutory framework—it is a moral and constitutional commitment to safeguard one of the most vulnerable sections of our society: children. Its enactment represented a much-needed departure from earlier, fragmented laws, by offering a comprehensive, gender-neutral, and victim-centric approach to the problem of child sexual abuse in India.

The Act has introduced clear definitions of sexual offences, child-sensitive trial procedures, mandatory reporting mechanisms, and a structure that compels institutions to act responsibly. It acknowledges not only the physical but also the psychological trauma that sexual abuse inflicts on children. Landmark judicial decisions, especially from the Supreme Court and High Courts, have played an essential role in expanding the scope of POCSO, interpreting its provisions in favour of child welfare, speedy justice, and preservation of dignity.

Yet, despite its strength on paper, POCSO faces several implementation challenges. Delays in investigation and trial, lack of trained personnel, societal stigma, low conviction rates, and the complex issue of consensual relationships among adolescents often undermine its effectiveness. In cases involving teenagers, the law—meant as a shield—sometimes risks becoming a sword of criminalisation, especially when applied without sensitivity to context.

Experts and child rights activists increasingly call for a more nuanced application, especially in distinguishing exploitative relationships from consensual ones. At the same time, the need for strict enforcement in genuine abuse cases remains non-negotiable.

Ultimately, the true success of POCSO lies not merely in the number of cases registered or convictions secured, but in the societal change it inspires. It demands that we, as a society, become more vigilant, more compassionate, and more proactive in defending children’s rights.

In sum, POCSO is not just a law; it is a living promise—a promise that every child in India should grow up in an environment free from fear, exploitation, and silence. For that promise to hold true, we must ensure not only legal compliance but also a collective cultural transformation towards child safety, dignity, and justice.

🔍 Understand the law. Empower the future.

📢 Share this piece to raise awareness about child protection and legal safeguards.

🌐 Read more thoughtful legal commentary at thinkingthorough.com

💬 Your perspective matters—join the dialogue on justice and reform across our platforms.

References

Admin. (2024, February 20). Protection Of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO Act). BYJUS. https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/pocso-act/

Government of India. (2012). THE PROTECTION OF CHILDREN FROM SEXUAL OFFENCES ACT, 2012. In THE PROTECTION OF CHILDREN FROM SEXUAL OFFENCES ACT, 2012. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2079/1/AA2012-32.pdf

Jain, G. (n.d.). Landmark Judgments under POCSO Act, 2012 and analysis. https://www.manupatracademy.com/assets/pdf/legalpost/Landmark-Judgments-Under-Pocso-Act.pdf

Mahawar, S. (2025, January 9). Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO), 2012. iPleaders. https://blog.ipleaders.in/pocso-act-everything-you-need-to-know/

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, July 30). Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protection_of_Children_from_Sexual_Offences_Act#:~:text=The%20Protection%20of%20Children%20from,1

Yadav, G. (2025, July 29). POCSO Act – salient features & challenges – explained Pointwise. Free UPSC IAS Preparation Syllabus and Materials for Aspirants. https://forumias.com/blog/pocso-act-significance-challenges-explained-pointwise/#:~:text=impact%20%26%20mental%20impact%20of,then%29%20existing%20provisions

Ambedkar, P. R. & Principal Civil Judge (Junior Division), Dhone. (2012). Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 – An Overview. https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ec030b6ace9e8971cf36f1782aa982a7/uploads/2024/09/2024092050.pdf

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012

What does POCSO mean?

POCSO stands for Protection of Children from Sexual Offences.

What is the age limit under the POCSO Act?

The Act applies to children below 18 years of age.

What is the full form of POCSO?

Protection of Children from Sexual Offences.