‘One Nation One Election’ (ONOE) is a bold electoral reform proposal being actively considered by the Indian government. The idea? To hold all elections—national, state, and local—together, either on a single day or within a short, defined timeframe.

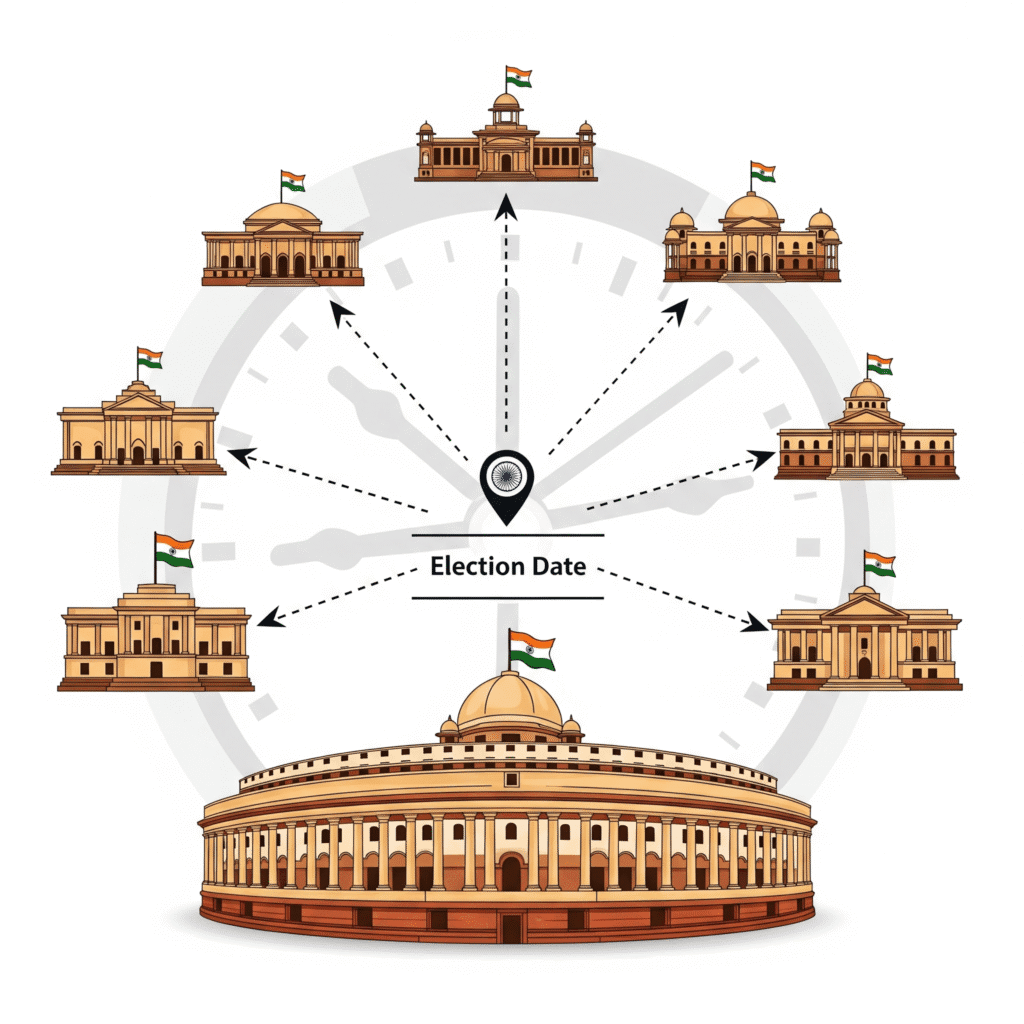

Under ONOE, Lok Sabha elections would be conducted in sync with state assembly elections across India’s 28 states and 8 Union Territories. The proposal even aims to align local body elections (Municipalities and Panchayats) within 100 days of these national and state polls—an unprecedented electoral overhaul.

But ONOE isn’t just about timing. It’s rooted in three major goals:

- Cutting election costs, which run into thousands of crores under the current staggered system.

- Reducing strain on the administrative machinery and security forces, who are constantly deployed for election duties.

- Ensuring policy continuity, by avoiding repeated imposition of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC), which often pauses new initiatives and delays development work.

Though simultaneous elections were the norm in India till the late 1960s, the idea has gained fresh momentum, especially since 2014, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi pushing strongly for its revival. High-level panels have since been formed to explore its feasibility, triggering intense legislative debates.

What sets ONOE apart is not just its cost-cutting appeal, but its vision of uninterrupted governance. The proposal reflects a deeper belief: that constant elections distract governments from long-term policymaking and fragment India’s developmental focus. By merging all elections into a unified cycle, ONOE hopes to steer the country toward stable, streamlined, and future-focused governance—though not without confronting serious legal and logistical hurdles.

A Look Back: When India Held Simultaneous Elections

Believe it or not, the idea of “One Nation, One Election” isn’t new. In fact, India began its democratic journey with synchronized elections. The first general elections in 1951–52 saw both the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies voting together, a pattern that continued smoothly through 1957, 1962, and 1967.

This harmony was possible partly because the Indian National Congress dominated the political landscape, enabling a more streamlined national focus on governance and development.

But things started to change in the late 1960s. Some state assemblies were dissolved prematurely in 1968–69, followed by the early dissolution of the Lok Sabha in 1970, triggering fresh elections in 1971. From then on, India’s elections became staggered. Over time, frequent dissolutions, mid-term polls, and even term extensions created a patchwork of election schedules, with some state or national poll happening almost every year.

This shift highlights a deeper truth about parliamentary democracies: instability, no-confidence motions, and coalition politics can disrupt even the best-laid election calendars. So, merely bringing in a law for simultaneous elections may not be enough—it would need strong constitutional safeguards to maintain continuity.

What’s more, the rise of regional parties and growing political diversity after the 1970s has made it even harder to synchronize elections today. Unlike the early years of single-party dominance, India’s current multi-party federal setup presents a more complex challenge—both legally and politically—for implementing ONOE now.

The Promise: Why Supporters Back Simultaneous Elections

Supporters of One Nation, One Election (ONOE) believe it could be a game-changer—saving money, improving governance, easing pressure on resources, and making democracy more engaging for the people. Here’s why they think it’s worth considering:

💰 Massive Savings for the Nation

Elections in India don’t come cheap. The 2019 Lok Sabha elections alone cost the government around ₹60,000 crore (approx. $7.2 billion)! Now imagine similar expenses being repeated across different states every year. With ONOE, all elections—Parliament, State Assemblies, even local bodies—could happen together, drastically cutting costs.

The Election Commission estimates that just one set of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) could be reused for three full election cycles over 15 years, saving over ₹10,000 crore. The idea is simple: spend less on elections, and invest more in development. Instead of pouring money into repeated polls, the same funds could go to schools, roads, or healthcare.

🏛️ Better Governance, Less Disruption

Every time an election rolls around, the Model Code of Conduct kicks in, freezing new policies and halting big announcements. This slows down governance and delays development.

ONOE promises fewer interruptions. Instead of always being in “campaign mode,” governments can focus on their core job—delivering results. Policy continuity and long-term planning become possible. Supporters argue that this would help break the cycle of stop-start governance and strengthen the link between a government’s mandate and its delivery.

🛡️ Less Burden on Officials & Forces

Frequent elections stretch India’s administrative and security systems thin. From district collectors to police personnel, thousands are pulled away from their regular duties for weeks—sometimes months.

If elections happen all at once, the deployment of security forces and election staff can be streamlined. They can return to their primary responsibilities—like maintaining law and order—sooner. For a country of India’s size and complexity, this could improve overall governance and reduce bureaucratic burnout.

🗳️ More Voter Energy, Less Fatigue

Voting is the backbone of democracy, but doing it too often can wear people out. With elections almost every year in some corner of the country, many voters experience what experts call “voter fatigue.”

ONOE aims to fix that by turning elections into a focused, meaningful event every five years. This could boost participation, enthusiasm, and even turnout. Fewer, better-timed elections may help citizens value their vote more, rather than seeing it as just another routine event.

The Perils: Concerns and Criticisms of One nation One election (ONOE)

While the “One Nation, One Election” (ONOE) idea sounds efficient on paper, it has sparked strong criticism from many corners of Indian democracy.

🧩 A Threat to Federalism?

One of the biggest worries is that ONOE could damage India’s federal structure. Critics say synchronizing elections could either cut short or forcefully extend state assemblies’ terms just to align them with Lok Sabha polls. This raises fears of states losing their autonomy.

Many regional parties see this as a power move by the Centre, potentially steering the system towards a more centralized or even presidential style of governance—weakening the vibrant multi-party democracy that India thrives on. National cycles might overshadow regional diversity, blurring India’s political mosaic into a one-size-fits-all framework.

🌐 Impact on Regional Parties

Regional parties fear they’ll be drowned out by the noise of national campaigns. If state and national elections are held together, voters may choose based on the popularity of national leaders rather than state performance. These risks reducing space for local voices and issues—core elements of a diverse federal democracy.

🗳️ Voter Behavior Shift

Holding all elections together might also confuse voters. Studies show that simultaneous polls can cause people to vote along national party lines instead of focusing on state-level issues. This dilutes regional representation and narrows the lens through which voters view governance—undermining the quality of democracy.

📉 Reduced Accountability

Frequent elections, though resource-intensive, allow voters to regularly hold governments accountable. ONOE would reduce this frequency, limiting citizens’ chances to express dissatisfaction mid-term. There are even concerns that it could lead to the weakening of mechanisms like no-confidence motions—tools vital for keeping governments answerable.

⚙️ The Logistical Mountain

Conducting one mega-election in a country with over 960 million voters, 1 million+ polling booths, and massive administrative diversity is no easy feat. From EVM procurement to deployment of forces, the operation would be colossal. It demands legal, financial, and constitutional overhauls—not to mention unprecedented coordination.

| Concern Category | Specific Criticism |

| Threat to Federalism | Potential erosion of state autonomy, centralization of power, and a move towards a unitary or presidential system. |

| Impact on Regional Parties | Marginalization of regional parties as national narratives overshadow local issues and concerns. |

| Voter Behavior | Risk of voters conflating national and state issues, leading to less informed decisions and skewing state election results. |

| Accountability Concerns | Reduced opportunities for voters to hold governments accountable, potentially impacting responsiveness; concerns about abolition of no-confidence motions. |

| Logistical Hurdles | Immense challenges in managing elections for over 960 million voters across 1 million polling stations simultaneously, requiring massive resources. |

The Road Ahead: Challenges & Solutions for One Nation, One Election

Implementing One Nation, One Election (ONOE) isn’t just a policy tweak—it’s a constitutional overhaul combined with a massive logistical operation.

Legal and Constitutional Hurdles

Bringing ONOE to life will require major constitutional amendments. The Ram Nath Kovind Committee proposed 18 changes, especially to:

- Article 83 & 172 – to align Lok Sabha and State Assembly terms

- Article 324A (new) – to allow simultaneous polls in Panchayats and Municipalities (needs state ratification)

- Article 325 – to empower the ECI for a common voter list and ID (also needs ratification)

Laws like the Representation of the People Act, 1951, and the Rules of Procedure for legislatures must also be amended. Achieving this will require a two-thirds majority in both Houses and consent from half the states—a tough ask, especially after the 2024 elections, where the ruling party lost some ground. So, political consensus is not just ideal, it’s essential.

| Article / Law | Current Provision (Brief) | Proposed Amendment / Impact |

| Article 83 | Duration of Houses of Parliament (normally 5 years) | To synchronize Lok Sabha term with state assemblies, potentially extending or curtailing terms. |

| Article 172 | Duration of State Legislative Assemblies (normally 5 years) | To align State Assembly terms with the Lok Sabha, potentially extending or curtailing terms. |

| Article 324A (New – Proposed by Kovind Panel) | — (New article) | To allow simultaneous elections for Panchayats and Municipalities; requires state ratification. |

| Article 325 | Relates to preparation of electoral rolls | To empower the ECI to create a common electoral roll and voter ID across all three tiers. |

| Representation of the People Act, 1951 | Governs the conduct of elections | Requires amendments to support synchronized election cycles and constitutional changes. |

| Rules of Procedure of Lok Sabha & State Assemblies | Procedural rules for legislative functioning | Must be amended to align with new synchronized election processes and timelines. |

Committee Recommendations at a Glance

- Law Commission (2018): Said ONOE needs amendments. Suggested:

- Advancing/postponing some elections to sync cycles

- Holding all elections in a year together if full sync isn’t possible

- Replacing no-confidence motions with constructive ones (you can only vote out a government if you have another ready to take over)

- Kovind Committee (2024): In its 18,000-page report, it suggested:

- Declaring an “Appointed Date” (e.g., 2029) post-elections as the new starting point

- Extending or shortening terms to match that date

- Two-phase implementation: first for Lok Sabha & State Assemblies, second for local bodies (within 100 days)

These suggestions are aimed at ending the cycle of mid-term dissolutions and election fatigue.

Tackling Mid-Term Breakdowns

A big concern: What if a government falls early?

The solution: Hold fresh elections only for the remainder of the five-year cycle.

So, if an assembly falls two years into its term, its replacement only serves three years.

Also proposed: Constructive no-confidence motions to ensure stability by allowing change only if a new government is ready.

Logistical Mammoth

This isn’t just about dates and votes—it’s also about machines, manpower, and money:

- Needed:

- 46.75 lakh Ballot Units

- 33.63 lakh Control Units

- 36.62 lakh VVPATs

- Estimated cost: ₹10,000 crore (every 15 years)

- Challenges:

- Training extra polling personnel

- Mass deployment of paramilitary forces

- More storage for EVMs

Clearly, it’s a nationwide exercise, not a routine poll.

One Electoral Roll to Rule Them All?

Both the Law Commission and Kovind Committee recommend a single electoral roll for Lok Sabha, Assemblies, and local bodies.

This would reduce duplication, empower the Election Commission, and streamline election planning—a crucial administrative fix.

Looking Abroad: What Can India Learn?

Countries like Sweden, South Africa, and Belgium hold synchronized elections, offering valuable lessons.

- Sweden: All elections (national, regional, municipal) held every 4 years. If a snap election happens, the new parliament serves the remainder of the original term.

- South Africa: National and provincial polls are held together every 5 years.

- Belgium: Holds federal and European Parliament elections together; sometimes aligns with regional elections.

However, these countries are smaller, more homogenous, and have different systems (like proportional representation), making their challenges very different from India’s.

India’s scale, diversity, and federal complexities mean we can’t copy-paste these models. Instead, our approach must be custom-built for Indian democracy—balancing ambition with practicality

Conclusion: Walking the Tightrope Between Efficiency and Democracy

The One Nation, One Election (ONOE) proposal stands at the intersection of ambition and complexity. At its core, ONOE promises a more streamlined electoral process, reduced public expenditure, and uninterrupted governance. By eliminating the frequent election cycle that currently consumes time, money, and focus, proponents argue that the government can redirect its energy toward long-term development goals and policy execution. The idea also has historical roots—India conducted simultaneous elections during its early decades, offering a glimpse of its past feasibility.

Supporters emphasize potential benefits:

- Massive cost savings in repeated election management

- Reduced burden on security and administrative machinery

- Greater stability for governance without constant political disruption

- Improved voter participation through a more consolidated and clear electoral process

However, behind the promise lies a deeply challenging landscape.

Critics voice legitimate concerns about the threat to federalism, warning that ONOE could tilt the balance of power further toward the Centre, marginalizing regional voices and reducing the autonomy of state governments. There’s also the fear that local issues may get drowned under dominant national narratives, potentially affecting the rise of grassroots-level leadership.

Moreover, reducing election frequency also reduces the opportunities for democratic feedback. Elections act as regular checkpoints where voters hold their governments accountable. Less frequent polls might delay this process, thereby affecting democratic responsiveness and weakening people’s voice in governance between cycles.

Logistically, the challenge is enormous. ONOE would require:

- Multiple constitutional amendments (including Articles 83, 172, 325, and the proposed 324A)

- Changes to electoral laws like the Representation of the People Act

- Amendments to parliamentary and assembly rules

- Consensus from both Houses of Parliament and ratification by at least 50% of the states

Proposals like shortened terms for governments that are formed after mid-term dissolutions aim to preserve synchronization but introduce new democratic questions. Would people accept a government elected for just 2 or 3 years? How would governance adapt to such fluctuating timelines?

Looking abroad, countries like Sweden, Belgium, and South Africa provide useful reference points for synchronized polls. But they function in smaller, more homogenous settings with different electoral systems. India’s scale—over 900 million voters, 28 states, 8 Union Territories, and a multiparty system—means our model must be uniquely Indian.

Ultimately, ONOE is not just a political or administrative reform—it’s a reimagining of how India conducts its democracy. Its success will depend on inclusive dialogue, bipartisan agreement, and a deep respect for the federal spirit enshrined in the Constitution. If India chooses to walk this path, it must do so not just with efficiency in mind, but with democratic integrity and diversity at heart.

The true test lies in balancing governance stability with democratic accountability, and in ensuring that every voice—from Delhi to the smallest Panchayat—continues to be heard, respected, and represented.

Share this article with your friends and family to keep them informed!

🔍 Explore More: https://thinkingthorough.com

📩 Let’s Connect: Have thoughts or suggestions? Drop us a message on our social media handles. We will be waiting to hear from you!!

References

One Nation, One Election – Wikipedia, accessed on July 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Nation,_One_Election

What is One Nation One Election, How Does it Work, Advantages …, accessed on July 12, 2025, https://cleartax.in/s/one-nation-one-election

One Nation, One Election – PIB, accessed on July 12, 2025, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2085082 Simultaneous Elections in India – Committee Reports, accessed on July 12, 2025, https://prsindia.org/policy/report-summaries/simultaneous-elections-in-india

(PDF) ONE NATION ONE ELECTION STREAMLINING INDIA’S ELECTORAL FUTURE – ResearchGate, accessed on July 12, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388994183_ONE_NATION_ONE_ELECTION_STREAMLINING_INDIA’S_ELECTORAL_FUTURE