The idea of human dignity and natural entitlements lies at the heart of every free society. Fundamental rights are not Favors given by rulers but universal safeguards that protect each person from unfair actions by the state. They ensure we live with freedom, respect, and justice. In a true democracy, these rights form the strong foundation on which government accountability, citizen welfare, and social harmony stand.

Why Fundamental Rights Matter

They are not just legal jargon; they are very important for our everyday life and shape the way our country grows:

- Protection from Misuse of Power

Governments have authority, but fundamental rights set clear limits on how they can use that power. For instance, the right to personal liberty ensures that no one can be detained without following proper legal procedures, and every person has the chance to present their case in court. - Encouraging Civic Participation

Rights such as freedom of assembly, speech, and expression allow people to discuss ideas openly, voice their opinions, and organise peaceful protests. This makes our democracy vibrant because leaders must listen to public views. - Adapting to Changing Needs

As society changes, courts interpret and expand rights. In recent years, landmark Supreme Court rulings have recognised the right to privacy, the right to a clean and healthy environment, and the right to equal treatment for all genders. This flexibility helps our Constitution stay relevant.

Together, these functions maintain a delicate balance: they secure individual freedoms while allowing the state to govern effectively for the common good.

Early Milestones in Global History

Long before modern constitutions, certain charters laid the groundwork for the freedoms we enjoy today. These documents emerged when people challenged rulers to respect basic human rights:

Magna Carta (1215)

- Historical Background

King John of England faced widespread anger for heavy taxes and harsh punishments. Nobles forced him to sign a charter at Runnymede in June 1215. - Important Features

- Declared that even the king must follow the law, a ground-breaking idea at that time.

- Introduced the concept of due process, meaning no free person could be punished without a proper trial by his peers.

- Long-Term Impact

Though it protected mainly nobles, the Magna Carta inspired later movements worldwide. It laid the basis for habeas corpus and influenced modern rule-of-law principles.

English Bill of Rights (1689)

- Turning Point

After the Glorious Revolution (1688), Parliament invited William and Mary to rule under new limits, leading to the English Bill of Rights in December 1689. - Key Provisions

- Freedom of Speech in Parliament: Members could debate without fear of royal intervention.

- Right to Petition: Citizens could formally ask the monarch to address grievances.

- Protection Against Cruel Punishment: No excessive bail or cruel and unusual punishment.

- Global Influence

This document directly inspired the American Bill of Rights (1791) and many other national charters, spreading ideas of civil liberties and checks on power.

These early milestones show a gradual widening of rights—from limited feudal protections to broad civil liberties—forming the backbone of democratic governance.

India’s Early Push for Rights

Inspired by global ideas, Indian leaders started drafting their own constitutional visions, demanding both political freedoms and social justice:

Swaraj Bill (1895)

- By: Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak.

- Main Proposals: Freedom of speech, equality before the law, and a basic legislative body. Though it never became law, it marked the first serious Indian effort to draft a self-governance constitution.

Nehru Report (1928)

- Purpose: To show that Indians could draft a complete constitution for themselves, responding to British doubts.

- Highlights: Suggested 19 Basic Rights, including freedom of religion, assembly, and protection against discrimination. This report provided a detailed blueprint that guided Constituent Assembly debates later on.

Indian National Congress Resolutions

- Lahore Session (1929): Under Jawaharlal Nehru’s leadership, the Congress declared Purna Swaraj (complete independence) as non-negotiable, stressing that true rights need a sovereign state.

- Karachi Session (1931): Combined civil-political rights with social-economic rights, such as free primary education, fair wages, and universal adult franchise. This holistic vision influenced the Directive Principles and Fundamental Rights in the Constitution.

Government of India Act (1935)

- Overview: Introduced provincial autonomy but omitted a separate chapter on rights. This gap highlighted the need for a comprehensive Bill of Rights in India’s own constitution.

These early efforts showed that Indian thinkers saw rights not only as political freedoms but also as tools for social and economic upliftment.

Crafting India’s Constitution

After World War II, India’s political journey accelerated towards a rights-based Constitution:

- Cripps Mission (1942)

The British government sent Sir Stafford Cripps to negotiate Indian cooperation in the war. Though it failed politically, it first acknowledged an Indian Constituent Assembly’s right to draft its own Constitution. - Cabinet Mission Plan (1946)

Laid out a three-tier government system and officially constituted the Constituent Assembly. It included safeguards for minority rights and federal principles. - Constituent Assembly Deliberations (1946–1950)

Diverse Membership: Included lawyers, social reformers, and political leaders from different regions and communities.

Special Advisory Committee: Chaired by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, it focused on drafting Fundamental Rights and balancing them with India’s social needs.

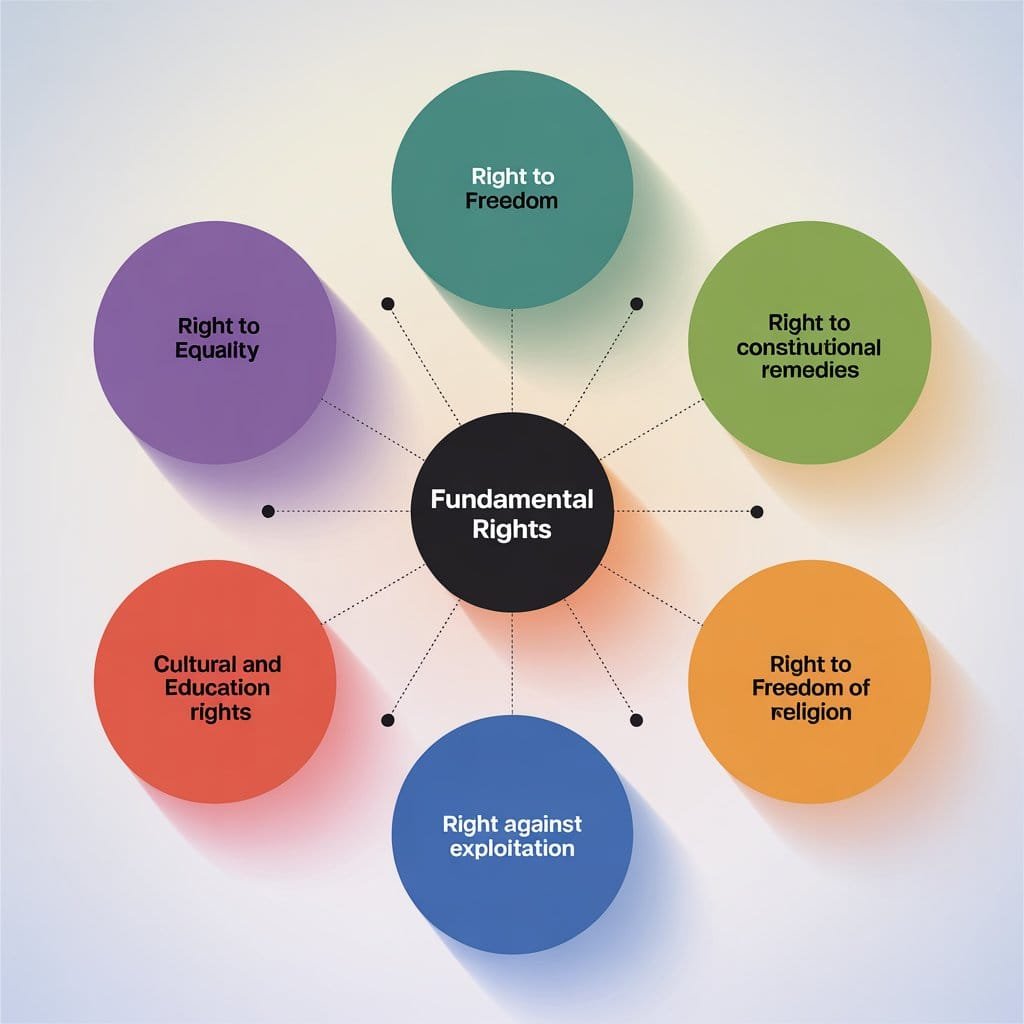

Final Outcome: Part III of the Constitution (Articles 12–35) enshrined seven justiciable rights, including: Right to Equality, Right to Freedom (speech, assembly, movement), Right against Exploitation (abolition of child labour and forced labour), Right to Freedom of Religion, Cultural and Educational Rights, Right to Constitutional Remedies , Right to life and personal Liberty.

Though the Right to Property was later removed, these rights form India’s Magna Carta, balancing individual liberty with collective welfare.

Fundamental Rights in the Indian Constitution

The Fundamental Rights, as enshrined in Part III of the Constitution (Articles 12-35), are often referred to as the Magna Carta of India, underscoring their foundational importance. A defining characteristic of these rights is their justiciable nature, meaning they are enforceable by courts, allowing aggrieved individuals to seek legal recourse for their violation.1

Key Features of Fundamental Rights

The Indian Constitution outlines several distinct features of its Fundamental Rights, which define their scope, limitations, and enforceability:

- Protected by Constitution: Unlike ordinary legal rights, these rights are explicitly protected and guaranteed by the Constitution itself, providing them with a higher status and greater sanctity.

- Not Sacrosanct, Permanent, or Absolute: While fundamental, these rights are not immutable or absolute. Parliament possesses the power to curtail or repeal them, but only through a constitutional amendment act. Furthermore, these rights are not absolute; the state can impose “reasonable restrictions” on their exercise. The crucial determination of whether a restriction is “reasonable” is ultimately decided by the courts, ensuring a check on potential executive overreach. This illustrates a careful balance where individual liberties are recognized but also operate within a framework that considers collective welfare.

- Justiciable: The enforceability of these rights is a cornerstone of their strength. Any aggrieved person can directly approach the Supreme Court (under Article 32) or the High Courts (under Article 226) for the enforcement of their Fundamental Rights if they are violated. This establishes the judiciary as the ultimate guardian of these rights, providing a crucial mechanism for their protection.

- Suspension: In times of national crisis, certain Fundamental Rights can be suspended. During the operation of a National Emergency, most of these Rights can be suspended, with the significant exceptions of the rights guaranteed by Articles 20 (protection in respect of conviction for offences) and 21 (protection of life and personal liberty). Moreover, the six rights guaranteed by Article 19 (freedoms of speech, assembly, association, movement, residence, and profession) can only be suspended when there is an external emergency (such as war or external aggression), and not on the ground of armed rebellion (i.e., internal emergency).

- Restriction of Application: To ensure the proper discharge of duties and maintenance of discipline, Parliament has the power (under Article 33) to restrict or abrogate the application of Fundamental Rights to members of armed forces, paramilitary forces, police forces, intelligence agencies, and analogous services. Similarly, their application can be restricted while martial law (military rule imposed under abnormal circumstances) is in force in any area (under Article 34).

- Parliament’s Exclusive Power: Article 35 vests the power to make laws to give effect to certain specified fundamental rights exclusively in the Parliament, and not in the state legislatures. This ensures uniformity in the application and enforcement of these crucial provisions across the nation.

Legacy and Ongoing Evolution

India’s Fundamental Rights are living principles, growing through court decisions and social action:

- Judicial Interpretation: The Supreme Court has expanded rights to include privacy (Puttaswamy case), environmental protection (MC Mehta cases), and LGBTQ+ rights (Navtej Singh Johar case).

- Grassroots Movements: Campaigns against caste discrimination, for women’s safety, and for disability and minority rights influence policy and strengthen constitutional guarantees.

- Future Challenges: Issues like data privacy, climate change, and digital speech will test and refine these rights further.

By securing individual freedoms and promoting social justice, Fundamental Rights remain the cornerstone of India’s democracy, guiding its path towards a more inclusive and just society.

To provide a clear overview of the scope and categories of these vital protections, the following tables delineate the main categories of Fundamental Rights and distinguish between those available to all persons and those exclusively for citizens.

| The Six Fundamental Rights of India | Articles |

| Right to Equality | 14-18 |

| Right to Freedom | 19-22 |

| Right against Exploitation | 23-24 |

| Right to Freedom of Religion | 25-28 |

| Cultural and Educational Rights | 29-30 |

| Right to Constitutional Remedies | 32 |

| Fundamental Rights: Citizens vs. All Persons |

| Available to Citizens Only |

| Prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth (Article 15) |

| Equality of opportunity in matters of public employment (Article 16) |

| Protection of the six fundamental rights of freedom mentioned in Article 19 |

| Protection of language, script and culture of minorities (Article 29) |

| Right of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions (Article 30) |

| Available to Citizens as well as Foreigners (except enemy aliens) |

| Equality before law (Article 14) |

| Protection in respect of conviction for offences (Article 20) |

| Protection of personal life and liberty (Article 21) |

| Right to elementary education (Article 21A) |

| Protection against arrest and detention in certain cases (Article 22) |

| Prohibition of human trafficking and forced labour (Article 23) |

| Prohibition of employment of children in factories (Article 24) |

| Freedom of conscience and free profession, practice and propagation of religion (Article 25) |

| Freedom to manage religious affairs (Article 26) |

| Freedom from payment of taxes for promotion of any religion (Article 27) |

| Freedom from attending religious instruction or worship in certain educational institutions (Article 28) |

📢 Share this article with your friends and family to keep them informed!

🔍 Explore More: https://thinkingthorough.com

📩 Let’s Connect: Have thoughts or suggestions? Drop us a message on our social media handles. We will be waiting to hear from you

References

Fundamental Rights (Part-1). (n.d.). Drishti IAS. https://www.drishtiias.com/to-the-points/Paper2/fundamental-rights-part-1

Fundamental Rights (Part-2). (n.d.). Drishti IAS. https://www.drishtiias.com/to-the-points/Paper2/fundamental-rights-part-2

Karishmamulani. (n.d.). History of fundamental rights included under Part III of the Constitution. https://gyansanchay.csjmu.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/History-Of-Fundamental-Rights-Included-Under-Part-III-Of-The-Constitution.pdf

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Fundamental Rights

How did Fundamental Rights evolve in the Indian Constitution?

The idea of Fundamental Rights in India was inspired by global charters like the Bill of Rights (USA), Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), and others. During the freedom struggle, Indian leaders strongly felt the need to protect civil liberties. So, when the Constitution was being drafted, the makers included a separate section on Fundamental Rights (Part III, Articles 12–35). These rights have evolved through constitutional amendments and landmark Supreme Court judgments like Kesavananda Bharati, Maneka Gandhi, and Golaknath, which expanded their scope and made them more meaningful.

Can Fundamental Rights be taken away or limited by the Government?

Fundamental Rights are not absolute – they come with reasonable restrictions to balance individual liberty and public interest. For example, freedom of speech does not allow someone to spread hatred or violence. During emergency situations, some rights like Article 19 (freedoms) may be temporarily suspended. However, after the 44th Amendment, the Right to Life and Personal Liberty (Article 21) cannot be suspended even during an emergency. Also, the judiciary plays a crucial role in ensuring that no government can misuse power to violate these rights.

What is the difference between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles?

Fundamental Rights are legally enforceable, meaning if they are violated, a person can go to court. Directive Principles of State Policy (Part IV of the Constitution), on the other hand, are non-justiciable – they are guiding principles for the government to create laws and policies for social welfare. While Fundamental Rights protect individual freedom, Directive Principles aim at building an equal and just society. Together, they create a balance between individual rights and collective good.