“The Constitution is not a mere lawyer’s document, it is a vehicle of Life, and its spirit is always the spirit of Age.” — Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution may appear short and simple, but its power is immense. It states:

“No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.”

Despite being just one sentence, it has become the soul of the Constitution—constantly growing, evolving, and adapting with time. What started as a narrow procedural safeguard has turned into a deep reservoir of human rights that protect almost every aspect of a dignified life.

This transformation reveals the dynamic character of our Constitution—a “living document”. Through judicial interpretation, Article 21 has been reimagined beyond its literal words to reflect society’s changing needs and moral values. It is a powerful example of how law can grow with people and times.

The Origins of Article 21: Two Words, Two Worlds

When our Constitution was being written, a major debate centered around two phrases:

- “Due process of law” (used in the U.S. Constitution), and

- “Procedure established by law” (eventually chosen for India).

Initially, the Advisory Committee had recommended the phrase “due process of law,” reflecting American influence. But the framers later decided to go with “procedure established by law.” Why?

They feared that “due process” would give the judiciary too much power to strike down progressive laws—like welfare schemes, labor laws, or land reforms—just as the U.S. Supreme Court did during the Lochner Era (1905–1937). The Indian leadership wanted to empower Parliament and the executive to build a new nation without constant judicial roadblocks.

B.N. Rau, one of the chief architects of the Constitution, consulted U.S. Justice Felix Frankfurter, who cautioned against giving courts such wide power. Instead, India adopted the more specific and rigid Japanese phrase— “procedure established by law”.

This choice meant that as long as a law was passed properly, even if it was unjust or unreasonable, it could still deprive a person of life or liberty. This approach showed clear trust in Parliament over courts. Also, given the chaos post-Partition, the state wanted flexibility to maintain public order—even if it meant preventive detention.

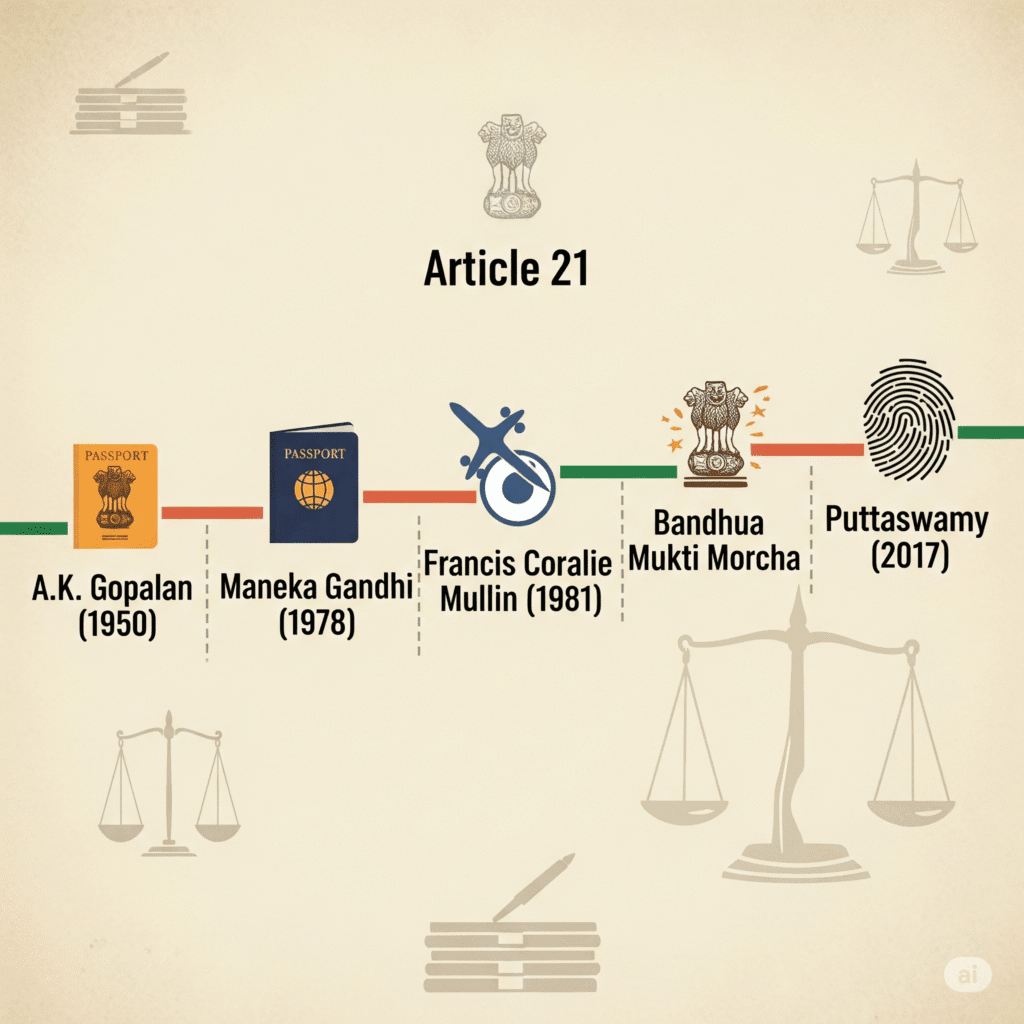

This design became clear in the landmark case of A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras (1950). The Supreme Court upheld a very narrow reading of Article 21: if the law was passed, it was valid—even if it was unfair. It also treated Articles 14 (equality), 19 (freedom), and 21 (life and liberty) as unrelated, limiting the Court’s ability to protect individuals from harsh laws.

So, early on, Article 21 had limited teeth. But that would soon change.

A Turning Point: Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978)

In 1978, a landmark case shook the foundations of Indian constitutional law. The government had confiscated journalist Maneka Gandhi’s passport without explanation. She challenged it, arguing that her fundamental rights were being violated.

This time, the Court refused to follow the narrow Gopalan view. In a stunning shift, it ruled that the “procedure” under Article 21 must be:

“Just, fair, and reasonable—not arbitrary, fanciful, or oppressive.”

This meant that laws could no longer simply follow technical rules—they also had to respect fairness and justice. This ruling brought in the spirit of “due process” into Indian law, even though the Constitution never used that phrase.

But the case did more.

The Supreme Court declared that Articles 14, 19, and 21 were interlinked—they formed a “Golden Triangle”. From now on, any action impacting life or liberty had to pass the tests of:

- Equality (Article 14)

- Freedom (Article 19)

- Fair procedure (Article 21)

This holistic approach created a strong shield for citizens against arbitrary state actions. The judiciary had firmly taken its place as the “watchdog of democracy.”

The Maneka Gandhi judgment thus completely changed the meaning of Article 21. It moved Indian constitutional law from blind obedience to procedure toward a rights-based, people-centered approach.

| Case Name | Year | Key Principle/Right Established |

| A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras | 1950 | Narrow procedural view; Articles 14, 19, 21 as distinct |

| Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India | 1978 | “Just, Fair, and Reasonable” procedure (substantive due process); Interlinking of Articles 14, 19, 21; Right to travel abroad |

| Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar | 1979 | Right to Speedy Trial |

| Francis Coralie Mullin v. Union Territory of Delhi | 1981 | Right to live with human dignity; includes basic necessities |

| Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation | 1985 | Right to Livelihood; Right to Shelter |

| M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (Ganga Pollution Case) | 1987 | Right to a Clean and Safe Environment |

| Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar | 1991 | Right to live in pollution-free environment (clean water and air) |

| Mohini Jain v. State of Karnataka | 1992 | Right to Education flows from Right to Life |

| Unnikrishnan v. State of Andhra Pradesh | 1993 | Right to Education as a fundamental part of Article 21 |

| Paschim Banga Khet Mazdoor Samity v. State of West Bengal | 1996 | Right to Health and Medical Aid |

| Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India | 1996 | Precautionary Principle and Polluter Pays Principle for healthy environment |

| Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan | 1997 | Right to a safe working environment (sexual harassment) |

| Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd) v. Union of India | 2017 | Right to Privacy as a fundamental right |

| Common Cause v. Union of India | 2018 | Right to Die with Dignity (passive euthanasia) |

| Ranjit Singh v. Union of India | 2024 | Right to be free from adverse effects of climate chang |

Expanding the Definition: What Does “Life” Really Mean?

“Right to life enshrined in Article 21 means something more than mere animal existence.”

— Justice P.N. Bhagwati, Francis Coralie Mullin v. Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi (1981)

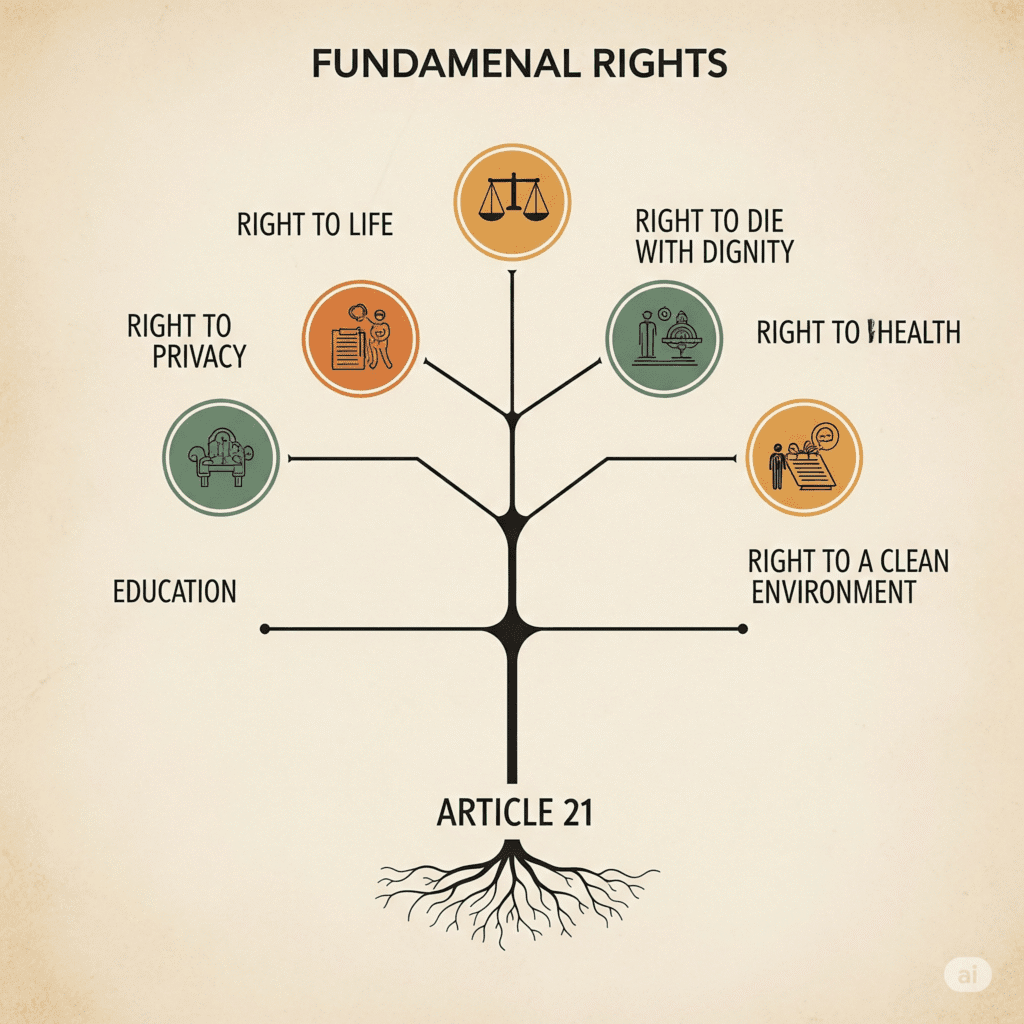

After the Maneka Gandhi case, the Supreme Court began to interpret the word “life” in Article 21 not as mere survival, but as a life of dignity. This new lens opened the doors for many more rights to be included under Article 21.

If dignity is essential for life, then the things required for dignity—like health, shelter, education, a clean environment—must also be part of the right to life.

This shift allowed the judiciary to respond to new challenges like pollution, poverty, lack of education, and even digital privacy, without needing new constitutional amendments.

Let’s look at how Article 21 has grown over the years:

- Right to Privacy: Recognized as a fundamental right implicit in Article 21, protecting citizens from unwarranted state surveillance and intrusion into personal matters. The Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017) judgment definitively declared privacy a fundamental right under Article 21.

- Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment: The right to life includes the right to live in a pollution-free environment, emphasizing environmental protection as crucial for human dignity. Landmark cases include Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar (1991), M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (Ganga Pollution Case, 1987) , and Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India (1996). Recent judgments also recognize the “right to be free from the adverse effects of climate change”.

- Right to Livelihood: Recognized as an essential component of the right to life, ensuring protection from arbitrary evictions that strip individuals of their means of living. This was notably established in Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985).

- Right to Health and Medical Aid: This includes access to healthcare facilities, essential medicines, and a healthy environment. Key cases include Paschim Bangla Khet Mazdoor Samity v. State of West Bengal (1996) and Pt. Parmanand Katara v. Union of India (right to emergency medical treatment).

- Right to Education: Recognized as fundamental for a dignified life, leading to legislative action. Landmark cases such as Mohini Jain v. State of Karnataka and Unnikrishnan v. State of Andhra Pradesh (1993) paved the way for the insertion of Article 21A (Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009).

- Right to Speedy Trial: An essential component of personal liberty, ensuring timely justice for every individual. This was established in Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar (1979).

- Right to Shelter and Food: Considered basic necessities for a dignified existence. These rights were affirmed in cases like Olga Tellis and Chameli Singh v. State Of U.P (1996).

- Other Significant Rights: The ambit of Article 21 continues to expand, encompassing rights such as the right to go abroad , the right against solitary confinement, handcuffing, and custodial death , the right to social justice and economic empowerment , the right to Doctors’ assistance , the right against delayed execution and public hanging , protection of cultural heritage , the right to die with dignity (passive euthanasia) , the right to sleep , the right to reputation , and the emerging right to internet access.

The Judicial Philosophy: Why the Expansion?

The story of Article 21 is not just about legal interpretation—it is about a living, breathing Constitution that evolves with time. The Indian judiciary has treated the Constitution as a “living document”, capable of growth and transformation in response to the changing needs of society. This idea rests on a belief that a constitution must serve not just the present, but also the future.

“The Constitution is not a parchment of paper, it is a vehicle of life, and its spirit is always the spirit of age.” — Justice P.N. Bhagwati

This philosophy lies at the heart of Article 21’s journey. Originally, the drafters of the Constitution chose to omit the phrase “due process” from Article 21, fearing judicial overreach. The early decision in A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras (1950) reflected this cautious, originalist approach. But as the decades passed, the judiciary realized that this rigid interpretation did not serve a rapidly changing society.

The landmark Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978) case changed everything. The Court declared that the procedure established by law must be “just, fair and reasonable,” effectively reintroducing substantive due process—something the framers had once avoided. This marked a paradigm shift from the letter of the law to the spirit of justice.

The expansion of Article 21 reflects this deliberate judicial choice: to prioritize human dignity and contemporary needs over historical rigidity. As a result, Article 21 has become one of the most interpreted and enriched provisions in the Indian Constitution.

However, this dynamism hasn’t been without criticism. The judiciary’s proactive stance, often termed judicial activism, has sometimes blurred the lines between the three pillars of democracy. When courts dictate policy on matters like environmental regulation, education, or healthcare, critics argue it amounts to judicial overreach. They question:

- Should unelected judges make decisions that impact public finances?

- Can courts effectively implement what they declare?

- Does this violate the principle of separation of powers?

Indeed, as Justice Chandrachud once acknowledged: “Judicial activism must remain within the bounds of judicial restraint.”

Still, the positive outcomes of this activism are undeniable. The judiciary has become the “watchdog of democracy”, ensuring that rights are not just written on paper but accessible to every citizen, especially the marginalized. The challenge now is maintaining a delicate balance—preserving the spirit of Article 21 without undermining democratic accountability.

| Right | Brief Description/Core Idea | Representative Case (if applicable) |

| Right to Live with Human Dignity | Beyond mere survival, includes basic necessities, freedom from humiliation, respect, and fulfillment. | Francis Coralie Mullin v. UT of Delhi |

| Right to Privacy | Protection from unwarranted state surveillance and intrusion into personal matters. | Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. UOI |

| Right to a Clean Environment | Right to live in pollution-free water, air, and surroundings. | Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar, M.C. Mehta v. UOI |

| Right to Livelihood | Protection from arbitrary actions that deprive individuals of their means of living. | Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation |

| Right to Health and Medical Aid | Access to adequate healthcare facilities, essential medicines, and emergency treatment. | Paschim Banga Khet Mazdoor Samity v. State of West Bengal |

| Right to Education | Fundamental for a dignified life; free and compulsory education for children (Art. 21A). | Mohini Jain v. State of Karnataka, Unnikrishnan v. State of Andhra Pradesh |

| Right to Speedy Trial | Ensures timely justice and prevents indefinite detention. | Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar |

| Right to Shelter | Necessary for a meaningful life, including appropriate living space and basic facilities. | Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation, Chameli Singh v. State of U.P. |

| Right to Food | Access to necessary nutrition for livelihood and dignified existence. | Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation |

| Right to Go Abroad | Freedom to travel and leave the nation. | Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India |

| Right to Sleep | A fundamental necessity for health and existence. | Ramlila Maidan Incident case |

| Right to Reputation | Essential component of living a decent life. | Board of Trustees’ case |

| Right to Internet Access | An evolving right in the digital age. | |

| Right to Die with Dignity | Upholding passive euthanasia as part of the right to life. | Common Cause v. Union of India |

Impact and Implications: Article 21 in Indian Society

Article 21, once narrowly confined to protection against unlawful detention, now touches every aspect of human life—from clean air and safe drinking water to education, healthcare, and even internet access.

Let’s look at how this expanded interpretation has reshaped Indian governance:

🌿 Environment

The right to a clean and healthy environment was recognized under Article 21 in several landmark cases like Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar (1991). More recently, courts have acknowledged the right to be free from the effects of climate change, compelling the government to introduce stronger pollution controls and environmental policies.

🏥 Health

The right to health, once absent from the constitutional text, is now central to state policy. Programs like Ayushman Bharat owe their existence to judicial directives recognizing health as a part of the right to life. Mental health has also come into focus under this expanded scope.

📚 Education

The Unnikrishnan v. State of Andhra Pradesh (1993) judgment recognized the right to education under Article 21, paving the way for the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009. This brought fundamental education into the core of state obligations, pushing for digital inclusion and equity.

🏠 Livelihood and Shelter

Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985) declared the right to livelihood and shelter as part of Article 21, significantly affecting how authorities approach urban eviction and migrant rights.

The ripple effects of these judgments go beyond courtrooms. Article 21 has become a policy driver—a constitutional lever compelling the State to act on issues it might otherwise neglect.

But even with all this progress, a harsh truth remains: many citizens still struggle to realize these rights in practice.

🚧 Gaps and Challenges

Despite a progressive legal framework:

- Rural populations face infrastructure deficits.

- Judicial delays obstruct timely justice.

- Bureaucratic indifference and lack of awareness hinder delivery.

- Socio-economic inequalities continue to marginalize the poor, women, transgender persons, migrant workers, and others.

The disconnect between law and reality is significant. Rights recognized in courtrooms don’t always translate into meaningful access. The implementation gap is where India’s constitutional aspirations often falter.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Article 21

The journey of Article 21 is a powerful reminder that the Constitution is not a relic of the past—it is a living promise for a just, equitable, and dignified life.

“Life is not merely the act of breathing; it is living with dignity.”

— Justice Dipak Misra, Common Cause v. Union of India (2018)

Through visionary judicial interpretation, Article 21 has evolved into the “heartbeat of the Constitution”, transforming Indian constitutionalism. It now binds the State to positive duties—ensuring clean air, quality education, public health, and social security for all.

Yes, challenges remain. Yes, judicial activism has its limits. But in the face of inequality, neglect, or injustice, Article 21 stands tall—as a shield for the vulnerable, a guidepost for policy, and a reminder that every Indian has the right to live not just to exist, but to thrive.

In this way, Article 21 continues to write the story of India’s constitutional dream—a story of life, liberty, and dignity for all.

Share this article with your friends and family to keep them informed!

🔍 Explore More: https://thinkingthorough.com

📩 Let’s Connect: Have thoughts or suggestions? Drop us a message on our social media handles. We will be waiting to hear from you!!

References

Admin. (2024, January 24). Right to Life (Article 21) – Indian Polity Notes. BYJUS. https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/right-to-life-article-21/

Asthana, S. (2024, July 29). Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. iPleaders. https://blog.ipleaders.in/article-21/

Constitution of India. (2023, March 31). Article 21: Protection of life and personal liberty – Constitution of India. https://www.constitutionofindia.net/articles/article-21-protection-of-life-and-personal-liberty/

Government of India. (n.d.). THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA (Part III. —Fundamental Rights. —Arts. 15-16.). In THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA. https://www.mea.gov.in/Images/pdf1/Part3.pdf

Rights under Article 21 of the Constitution. (n.d.). Drishti Judiciary. https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/current-affairs/rights-under-article-21-of-the-constitution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Article 21

What does Article 21A refer to?

Article 21A was added by the 86th Constitutional Amendment Act, 2002, and it specifically deals with Right to Education.

It reads:

"The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of six to fourteen years in such manner as the State may, by law, determine."

This means that every child between 6 and 14 years has a fundamental right to free and compulsory education, and it is the State's duty to ensure this through proper schools, teachers, and infrastructure.

It works in harmony with Article 21, reinforcing that a life with dignity begins with basic education.