In India, the word “reservation” is not just a dry policy term—it is a spark that ignites hope, debate, and strong emotions. For many, it is seen only as a quota system in education and government jobs. But the truth is, its journey is far more layered. It reflects a nation’s struggle with a social hierarchy thousands of years old, and its bold attempt—through the Constitution—to create an egalitarian society. Reservation is not a static rulebook; it is an ongoing narrative of justice, conflict, and evolution.

At its very core, reservation—often called affirmative action or positive discrimination—is a corrective tool. It was formally launched in 1950, making it one of the oldest and most extensive programs in the world. Its aim was simple but powerful: to provide a ladder of opportunity to communities historically pushed to the margins, and to open doors in education, employment, and governance.

But this journey has always carried a deep tension. On one side, the Indian Constitution guarantees “equality before the law” and bans discrimination against individuals. On the other, it carries special enabling provisions that allow the state to actively support disadvantaged communities. The history of reservation is therefore a constant balancing act—between individual equality and group justice. Far from being an exception to equality, reservation is seen as a step towards substantive equality in a society marked by deep-rooted disparities.

The First Stirrings: Seeds of Affirmative Action Before 1947

The story of reservation did not begin in 1950. Its roots stretch back into the late 19th century, shaped both by Indian social reformers and British colonial policies.

The earliest demand came as far back as 1881, when Jyotirao Phule argued for positive discrimination in 1882. Long before the Indian state acted, some progressive princely states began experimenting with reservation. The pioneer was Chhatrapati Shahu, Maharaja of Kolhapur, who in 1902 introduced a bold policy reserving 50% of state services for non-Brahmin and backward classes, directly challenging the dominance of a single community in administration.

Inspired by this, the Mysore state, after a long social justice movement, set up a committee in 1918 and implemented reservations for non-Brahmins in 1921.

At the same time, the British government pursued its own version of group representation—but for very different motives. The Morley-Minto Reforms (Government of India Act, 1909) introduced separate electorates for Muslims. Later, this was extended to other communities. Unlike Indian reformers, who sought reservation as a tool of social justice, the British used it as an administrative mechanism to manage diversity—and, as many historians argue, to weaken the rising tide of Indian nationalism.

By the 1920s, these two streams—bottom-up struggles for social equity and top-down colonial policies of control—had converged. In 1921, the Justice Party government in Madras Presidency issued the first Communal Government Order, which by 1927 had evolved into a detailed quota system.

Thus, by the time India prepared to frame its own Constitution, the idea of reservation was no longer new—it was already a powerful political reality.

A Clash of Titans: Gandhi, Ambedkar, and the Poona Pact

One of the most dramatic turning points in the early history of reservation in India came in 1932, when two towering figures of modern India—Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar—stood on opposite sides of an intense ideological battle.

The spark was lit when British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald announced the Communal Award, which proposed separate electorates for minorities, including the Depressed Classes (today known as Scheduled Castes).

Under this system, members of the Depressed Classes would elect their own representatives in special constituencies, while also retaining a second vote in the general constituencies. For Dr. Ambedkar, a visionary jurist and the most powerful voice of the Depressed Classes, this was a non-negotiable tool of empowerment. He argued that the double vote would ensure accountability, allowing Dalit representatives to truly stand for their community, free from the dominance of the upper-caste led Congress Party.

But Gandhi strongly disagreed. To him, separate electorates threatened to permanently divide the Hindu community and isolate the Depressed Classes from the larger social fabric. To resist, he launched a “fast unto death” at Yerwada Jail, Poona, a move that shook the entire nation. The atmosphere turned electric—millions anxiously followed the Mahatma’s health, as his life hung in the balance.

Faced with enormous moral and political pressure, Ambedkar was compelled to negotiate. The outcome was the historic Poona Pact of 1932—a monumental compromise. Ambedkar gave up the demand for separate electorates, but in return secured joint electorates with reserved seats. This meant all voters—upper castes and Depressed Classes alike—would vote together, but certain seats would be reserved exclusively for Depressed Class candidates. Importantly, as part of this agreement, their representation in provincial legislatures was nearly doubled—from 71 under the Communal Award to 148.

The Poona Pact was not just a political deal; it shaped the future of Dalit political representation in India. On one hand, it guaranteed Dalit leaders a place in legislatures. On the other, it required them to gain acceptance from the wider electorate, which encouraged integration. Yet, it also created a subtle challenge: candidates seen as “too radical” by the majority could struggle to win. This complex legacy of Ambedkar and Gandhi’s clash still echoes in debates today.

Forging a Republic’s Conscience: The Constituent Assembly Debates

As India stood on the brink of independence, the responsibility of drafting a new Constitution fell on the Constituent Assembly. Here, leaders wrestled with difficult but vital questions: What kind of republic should India be? And crucially—what role should reservation play in building a democratic and egalitarian society?

The mood inside the Assembly was one of idealism—to create a just, egalitarian society. Yet, there was also a sober recognition of the deep inequalities India had inherited. Discussions on minority rights, often led by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and others, saw impassioned arguments. Leaders from the Depressed Classes, like S. Nagappa, pressed hard for proportional representation in legislatures and government, insisting it was a necessary safeguard for their survival and dignity.

A key consensus that emerged was to make political reservations for SCs and STs a temporary measure. The Constitution set a ten-year limit, after which the policy would be reviewed. The framers hoped that in a decade, society would progress enough to make such measures unnecessary. Yet, history has unfolded differently—this “temporary clause” has been extended every ten years, ensuring that reservation remains an enduring and central theme of Indian politics.

One of the most consequential debates was around reservation in public employment. The draft version of what would become Article 16(4) allowed the state to provide reservations for any “backward class of citizens.” Some members objected, calling the phrase too vague and open to misuse. They suggested restricting it only to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. But Dr. Ambedkar and the drafting committee stood firm, arguing for the broader term. This was a strategic and visionary choice—it recognized that backwardness in India was not confined to SCs and STs, and it gave future governments constitutional flexibility to identify and uplift other disadvantaged groups.

This foresight was strengthened by Article 340, empowering the President to appoint commissions to study the conditions of “backward classes” and recommend measures for their advancement.

Thus, the Constitution laid down a foundational framework for reservation, anchored in multiple provisions:

- Article 15(4): Added by the First Amendment, 1951, allowing special provisions for socially and educationally backward classes or SCs and STs.

- Article 16(4): Permitting reservation in public employment for any backward class not adequately represented.

- Article 46: A Directive Principle of State Policy directing the state to promote educational and economic interests of weaker sections, especially SCs and STs.

- Articles 330 & 332: Guaranteeing reserved seats in Lok Sabha and State Assemblies for SCs and STs.

Together, these debates and decisions forged not only a Constitutional safeguard but also a moral vision—that India’s republic would not ignore its most vulnerable, but actively work to bring them into the fold of equality and justice.

The Story Expands: The Mandal Revolution and the Rise of OBCs

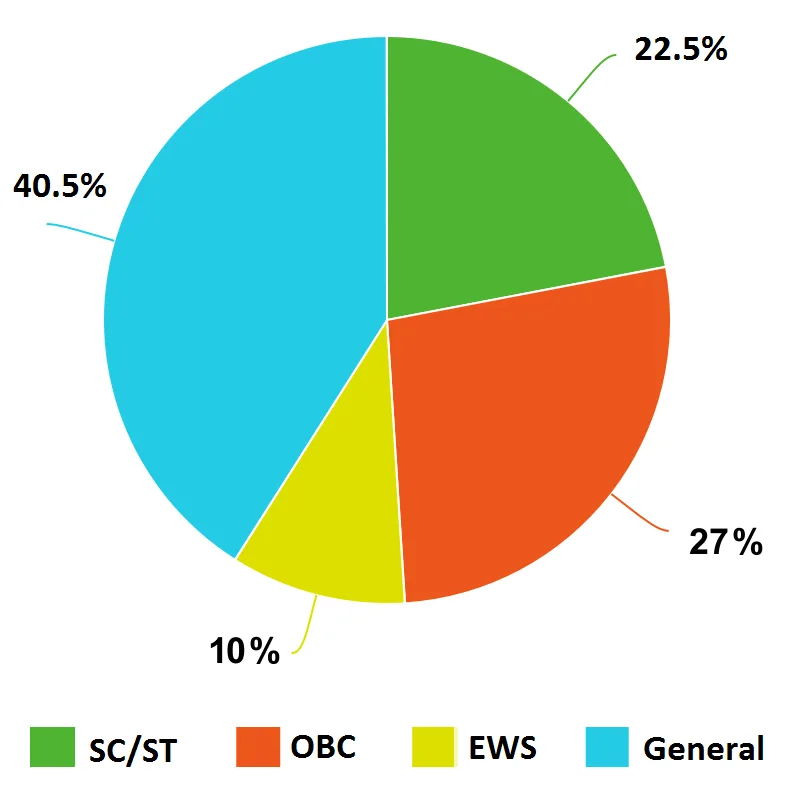

For the first few decades after independence, the policy of reservation was largely centered on the Scheduled Castes (SCs) at 15% and the Scheduled Tribes (STs) at 7.5%. But the next major chapter in India’s reservation journey unfolded with the focus shifting towards a vast and diverse group known as the Other Backward Classes (OBCs).

The foundation for this shift was laid in Article 340 of the Constitution, which empowered the government to investigate the conditions of socially and educationally backward classes. Acting under this mandate, the first attempt came in 1953 with the First Backward Classes Commission, chaired by Kaka Kalelkar. The commission identified more than 2,300 backward communities, using caste as the primary criterion. Yet, the report faced disagreements even within the commission itself. The Jawaharlal Nehru government rejected it, expressing discomfort with relying solely on caste as the marker of backwardness. As a result, the report was shelved, leaving the issue unresolved.

For more than two decades, the question of OBC reservation lay dormant. It resurfaced in 1979, when the Janata Party government set up the Second Backward Classes Commission, headed by B.P. Mandal. Unlike its predecessor, the Mandal Commission conducted an exhaustive nationwide survey, using 11 social, educational, and economic indicators to measure backwardness. Its report, submitted in 1980, concluded that OBCs made up nearly 52% of India’s population. To address their severe underrepresentation in jobs and education, the commission made a historic recommendation: 27% reservation for OBCs in central government employment and educational institutions.

But politics stalled its implementation. For ten years, the Mandal report gathered dust—until August 1990, when Prime Minister V.P. Singh announced its enforcement. The decision ignited one of the biggest social and political upheavals in modern India. Cities across northern India erupted in protests, led largely by upper-caste students, who saw the move as an attack on meritocracy. On the other hand, millions welcomed it as a long-overdue step towards social justice, sparking powerful counter-mobilizations.

The Mandal moment was more than just a policy change—it was a watershed in Indian democracy. It broadened the definition of “backwardness,” which until then was tied mostly to untouchability (SCs) and geographic isolation (STs). By including intermediate castes who were socially and educationally disadvantaged, reservation now became the tool of a much larger population. The impact went beyond education and jobs: it reshaped Indian politics itself, fueling the rise of strong regional parties rooted in OBC support and making caste-based mobilization a central axis of electoral competition.

The Gavel and the Law: How the Supreme Court Shaped the Policy

The political firestorm unleashed by the Mandal Commission inevitably found its way to the Supreme Court. The legal battle culminated in the landmark case Indra Sawhney & Others v. Union of India (1992), decided by a nine-judge bench—one of the largest in the court’s history.

Delivered in November 1992, the verdict became a turning point in constitutional law, carefully balancing the ideals of equality with the need for affirmative action. The judgment laid down three historic principles that continue to define reservation policy today:

- The 27% OBC Quota was Upheld: The Court validated the government’s decision, affirming that caste can be a valid basis or at least a starting point to identify “social and educational backwardness.” This gave constitutional approval to the Mandal methodology.

- The 50% Ceiling was Established: To prevent reservations from becoming open-ended, the Court ruled that the total reservation cannot exceed 50% of available seats or posts. This ceiling was justified as a balance between the right to equality of opportunity and the state’s duty to uplift the disadvantaged.

- The “Creamy Layer” Principle was Introduced: In a groundbreaking move, the Court directed that the more affluent and advanced members of OBCs—the so-called “creamy layer”—should be excluded from reservation benefits. The idea was to ensure that the gains of affirmative action actually reached the poorest and most disadvantaged.

The Indra Sawhney judgment was an act of judicial statesmanship. Rather than fanning the flames, the Court crafted a durable constitutional framework that gave something to both sides: legitimacy to OBC reservations, yet safeguards to prevent excess. In doing so, it stabilized a deeply divisive issue and reinforced the judiciary’s role as the final arbiter in India’s reservation policy.

Today, every debate on reservation—whether about new quotas, extension of benefits, or the boundaries of affirmative action—must be measured against the principles set out in Indra Sawhney. It remains the bedrock of India’s reservation jurisprudence, bridging the difficult space between justice, equality, and politics.

| Year | Milestone | Significance |

| 1902 | Kolhapur Reservation | Chhatrapati Shahu of Kolhapur introduces 50% reservation for backward classes, a pioneering indigenous affirmative action policy. |

| 1932 | The Poona Pact | A compromise between Gandhi and Ambedkar establishes reserved seats for Depressed Classes within a joint electorate, setting the template for political reservation. |

| 1950 | Constitutional Enactment | The Constitution of India provides for reservation for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in legislatures, government jobs, and education. |

| 1990 | Mandal Commission Implemented | The V.P. Singh government implements the Mandal report, providing a 27% quota for Other Backward Classes (OBCs), leading to a major political and social realignment. |

| 1992 | Indra Sawhney Judgment | The Supreme Court upholds the OBC quota but introduces two crucial checks: the 50% ceiling on total reservations and the “creamy layer” exclusion principle. |

| 2019 | EWS Reservation | The 103rd Constitutional Amendment introduces a 10% quota for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS), marking a significant shift towards an economic criterion for reservation. |

The Narrative Today: New Chapters and Unanswered Questions

The story of reservation in India is far from complete. New developments and fresh questions continue to reshape this debate in the 21st century, adding layers of complexity to an already long journey.

One of the most significant milestones in recent years was the 103rd Constitutional Amendment Act, 2019. For the first time in India’s history, economic backwardness alone became the basis for affirmative action. This amendment introduced a 10% quota for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) among citizens who were not already covered by SC, ST, or OBC reservations.

Eligibility was defined by clear criteria: families with an annual income below ₹8 lakh and subject to certain property restrictions. This marked a philosophical shift—reservation was no longer just about correcting historical, caste-based discrimination, but also about addressing contemporary individual economic distress.

The law was immediately challenged. However, in 2022, the Supreme Court, in a 3:2 majority verdict in Janhit Abhiyan v. Union of India, upheld the amendment’s validity. The Court ruled that the 50% ceiling set in the Indra Sawhney (1992) case was not absolute and did not apply to the EWS quota. This created a new precedent, expanding the constitutional imagination of reservation.

But this new chapter has opened the floodgates for fresh debates that are shaping the future:

- The Demand for a Caste Census: Advocates insist that a nationwide caste census is essential, since the last one was conducted in 1931. Updated data, they argue, is crucial to understand the true socio-economic status of communities, especially OBCs, and to design a fairer reservation system. Opponents fear it may reinforce caste identities and intensify political polarization.

- Sub-Categorization of OBCs: Within the 27% OBC quota, evidence shows that a few dominant castes corner a disproportionate share of the benefits. To fix this imbalance, there is a strong push for sub-categorization. The Justice G. Rohini Commission (2017) reported that just 10 OBC communities had captured nearly 25% of all reserved jobs and admissions.

- Reservation in the Private Sector: With shrinking opportunities in the public sector, the debate has expanded to whether private companies should also adopt reservation. Supporters argue that since private industries benefit from public resources, they should shoulder responsibility for inclusive growth. Critics, however, worry this could compromise meritocracy, efficiency, and corporate independence.

Conclusion: An Unfinished Story

The journey of reservation has been long, complex, and deeply contested. What began as early experiments in princely states like Kolhapur and Mysore, took definitive shape in the Poona Pact (1932), and was later enshrined in the Constitution by India’s founders. It expanded dramatically through the Mandal Commission, which was both validated and balanced by the Indra Sawhney judgment (1992). And now, with the EWS quota, the debate has entered a new phase where economic criteria join caste-based concerns.

Yet, this remains a story without a final chapter. Reservation is still evolving, constantly tested by India’s struggles with inequality, identity, and justice. It mirrors the nation’s ongoing quest to fulfill the constitutional vision of liberty, equality, and fraternity—the ideals that Dr. B.R. Ambedkar so passionately articulated.

Far from signaling policy failure, the continuous debates over reservation reflect the vibrancy of Indian democracy—a society that refuses to shy away from its deepest challenges. In truth, the story of reservation is the story of India itself: unfinished, imperfect, but always striving toward a more inclusive and just future.

📢 Keep the conversation alive. 🌐 Read more insights at thinkingthorough.com

References

Chandra, M., & Kumar, P. (2023). Reservation Policy in India Scope, Development, History and Employment Rights. International Journal of Human Rights Law Review, 2(4), 1–58. https://humanrightlawreview.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Reservation-Policy-in-India-Scope-Development-History-and-Employment-Rights.pdf

vajiramandravi. (2025, February 7). Reservation – Part i. Vajiram and Ravi. https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-exam/reservation-part-i/

Government of India, Ministry of Heavy Industries & Public Enterprises, Department of Public Enterprises, & Nsu, F. (2016). Brochure on reservation for SCS/STs and OBCs. In Government of India [Report]. https://dpe.gov.in/sites/default/files/Reservation_Brochure-2.pdf

Rishabh. (2024, August 3). Understanding the origins of the reservation system in India. Sleepy Classes IAS. https://sleepyclasses.com/understanding-the-origins-of-the-reservation-system-in-india/

Chart 1 Credit : By Self – Own work [1], CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84578530