Freedom is something we often take for granted—until it’s taken away. The ability to speak our minds, gather with others, or choose where we live and work might seem like everyday things. But these simple acts are made possible because of the rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution, especially Article 19.

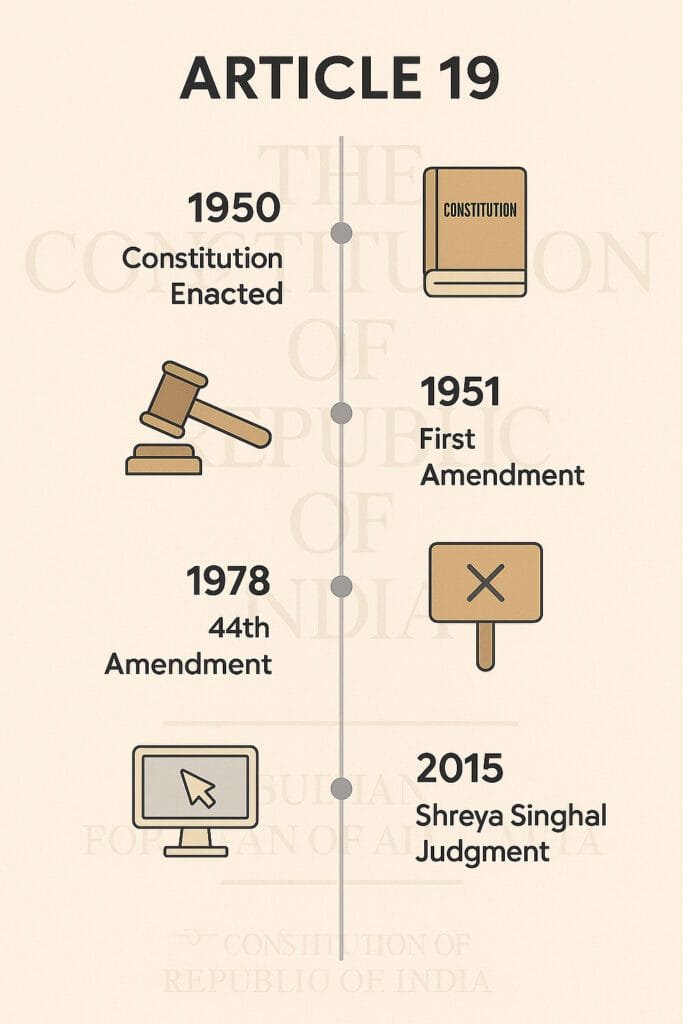

When India became a republic in 1950, the makers of the Constitution knew that a true democracy needed more than just elections—it needed personal freedoms. Article 19 was designed to give every citizen a set of basic rights that would protect individual voices, ideas, and choices. It was a direct response to the years of colonial rule, where speech was silenced, protests were crushed, and people had little control over their lives.

Since then, Article 19 of Indian Constitution has played a central role in shaping modern India. It has been at the heart of major court cases, public debates, and constitutional changes. It has protected journalists, students, artists, workers, and ordinary citizens whenever their freedoms were under threat.

In this article, we’ll explore the full journey of Article 19 (Fundamental Right of Freedom) —from its origin in 1950 to the present day. We’ll look at what each freedom means, how they’ve been challenged or defended over the years, and why these rights still matter today. Whether you’re a student, a scholar, or simply someone curious about how our rights work, this is a story worth knowing.

The Original Freedoms in Article 19 of Indian Constitution

In 1950, Article 19(1) guaranteed seven fundamental freedoms to every citizen (now six, after 1978). In everyday terms, these were: the right

- to freely speak, write or express opinions (speech and expression),

- to assemble peaceably and without arms,

- to form associations, unions or cooperative societies,

- to move freely throughout India,

- to reside and settle in any part of India,

- to practice any profession or to carry on any occupation, trade or business,

- and originally a right “to acquire, hold and dispose of property.”

As amended, Article 19 now reads only (a)–(e) and (g) above. (The property clause, formerly Art.19(1)(f), was deleted by the 44th Amendment, 1978.) In effect, Article 19 today protects six core freedoms. In simple English:

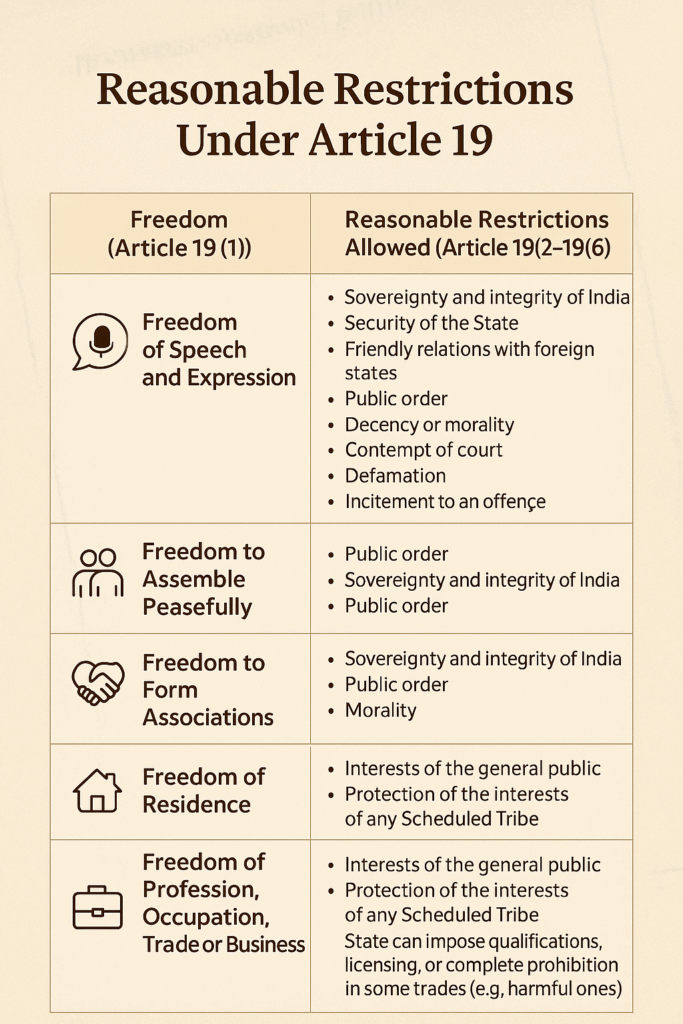

- Freedom of Speech and Expression (Art.19(1)(a)): Every citizen can voice opinions, write, publish or broadcast ideas without prior censorship. This includes a “freedom of the press,” as the Court observed in Romesh Thappar: “freedom of speech and of the press lay at the foundation of all democratic organisations…”.

- Freedom of Assembly (Art.19(1)(b)): Citizens may gather peacefully (without arms) for meetings, demonstrations or processions.

- Freedom of Association (Art.19(1)(c)): Citizens may form unions, political parties, cooperatives or other groups. (Notably, Article 19(1)(c) specifically protects even co-operative societies.)

- Freedom of Movement (Art.19(1)(d)): Citizens may travel freely anywhere across India.

- Freedom of Residence (Art.19(1)(e)): Citizens may live or settle in any part of the country.

- Freedom to Practise Occupation/Trade (Art.19(1)(g)): Citizens may pursue any lawful profession, trade or business of their choice.

Originally, Article 19(1) also included the right to property (to buy, own or sell land or assets). But this right was removed from the Fundamental Rights in 1978, reflecting a shift towards land reforms and socialism. (Property is now a mere legal right under Article 300A.)

Each of these freedoms is subject to “reasonable restrictions” by law – the Constitution itself lists grounds in clauses (2)– (6). For example, the state may curb speech for interests like “sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, contempt of court, defamation or incitement”. Similarly, restrictions on assembly or movement must be justified by public order or the general public’s interest. These limitations have long been hotly debated (see below).

Constitutional Amendments Affecting Article 19

Over the decades, several landmark amendments changed Article 19’s shape:

- First Amendment (1951): Within a year of the Constitution, Parliament narrowed free speech. Notably, it added “incitement to an offense” and “friendly relations with foreign states” as new restriction grounds in Art.19(2). It also stipulated that speech may be limited for “public order” or morality, reflecting concerns (after early court cases like Romesh Thappar) about broad press criticism.

- Amendments 24th–26th (1971–1972): In response to land-reform and property cases, Parliament amended fundamental-rights and Art.31 clauses. While these did not directly alter Art.19(1), they affirmed that land ceiling and acquisition laws (which affect property rights) could override FRs. (For example, Parliament got power to amend fundamental rights via Article 368 – 24th Amend – and to protect pre-1970 land laws – 25th Amend.)

- Forty-second Amendment (1976): Enacted during the Emergency, it added Art.358, explicitly suspending most Article 19 rights during proclamation of emergency. (In practice 1975–77, citizens’ speech, movement and association freedoms were curtailed.)

- Forty-fourth Amendment (1978): Strongly re-asserting citizens’ rights after the Emergency, it deleted Article 19(1)(f). In other words, the right to property ceased to be fundamental. The 44th Amendment act states this change “would not affect minority educational rights” but gave no more constitutional protection to ordinary private property.

- Ninety-seventh Amendment (2011): This law sought to boost cooperatives by explicitly inserting “co-operative societies” in Article 19(1)(c) and adding a Directive (Art. 43B) on autonomy of co-ops. However, the Supreme Court later struck down key parts of the 97th Amendment in 2021, holding that Parliament needed state ratification to alter provincial matters (cooperatives are a state subject). (The Court’s ruling left the original 1950 protection of cooperatives intact, but illustrates recent debates on Article 19’s scope.)

These amendments show Article 19 has been both shaken and fortified by political change. From the 1950s onward, lawmakers often tightened permissible restrictions (on speech or business) in the name of order; by the 1970s, they even sacrificed the property right in favour of wider social goals. Later reforms, especially after 2010, tried to extend rights in new areas (like co-ops), although judicial review has checked some of these moves.

Landmark Supreme Court Cases on Article 19

The Supreme Court of India has interpreted and expanded Article 19 in dozens of major cases. Highlights include:

- Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950): Foundation of free speech. Soon after 1950, the Court struck down a state ban on a journal’s distribution. Justice Fazl Ali famously wrote that “freedom of speech and of the press lay at the foundation of all democratic organizations”. This case established that the right to circulate ideas is intrinsic to Art.19(1)(a) and must be guarded against broad restrictions.

- Bennett Coleman & Co. v. Union of India (1972): Free press as public right. This case challenged government limits on newspaper ownership. The Court held that freedom of the press is part of the people’s right to free speech. It emphasized that “Freedom of the press is both qualitative and quantitative. Freedom lies both in circulation and in content.”. In short, government actions that unduly restrict publication or distribution violate Article 19’s promise of open expression.

- State of U.P. v. Raj Narain (1975): Right to know. In this case (following the 1974 revelations on electoral finances), the Court observed that citizens have a “right to know” what their government does, deriving from free expression. Article 19(1)(a) was interpreted to include seeking and imparting information about public affairs. This principle underpins modern transparency (e.g. RTI) and made “access to information” a facet of Article 19’s free speech.

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978): Golden Triangle and due process. Although centered on Article 21 (personal liberty) — Maneka’s passport was impounded — the Court explicitly linked Articles 14, 19 and 21. Justice Bhagwati held that laws depriving “personal liberty” must be “just, fair and reasonable,” not arbitrary. By overruling earlier narrow views, Maneka established that fundamental rights must be read together: any law affecting life or liberty must satisfy Articles 14, 19 and 21 as a “golden triangle.” Practically, this meant, for example, that restrictions on movement (Art.19) or passports must meet fair procedure standards. In short, Maneka greatly expanded due process, indirectly reinforcing Article 19’s freedoms by subjecting all laws to strict judicial scrutiny.

- Bijoe Emmanuel v. State of Kerala (1986): Freedom not to express. Three schoolboys were punished for not singing the national anthem due to religious beliefs. The Court held that Article 19(1)(a) includes a “right to remain silent.” Citizens cannot be forced to express views against their conscience. (While a brief mention here, this case shows Article 19 protects both speech and the choice of silence.)

- Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015): Speech in the digital age. A landmark modern case, Shreya Singhal struck down Section 66A of the IT Act, which had criminalized “grossly offensive” online messages. The Court unanimously declared 66A entirely unconstitutional, holding that it violated Article 19(1)(a) due to its vague and overbroad language. The judgment emphasized that mere “annoyance” or “insult” are not valid grounds for restricting speech, and that internet communication deserves strong protection. In effect, Shreya Singhal expanded free speech by curbing an excessive restriction: it guaranteed that citizens could post criticisms online without fear of arbitrary arrest.

- Other notable decisions: Excel Wear v. Union of India (1979) (validating the right to run a business, including shutting it down, under Art.19(1)(g)); Sankari Prasad (1951) and Golak Nath (1967) (on Parliament’s power to amend FRs); Arup Bhuyan (2013) and Naga Peoples’ Movement (2013) (expanding press freedom and right to information); Kedar Nath v. Bihar (1962) (upholding sedition law with limits – see below); among many others. Each case has fleshed out what “freedom” means in practice.

Together, these rulings illustrate a dynamic evolution: early judgments like Romesh built a strong core of free speech; later ones like Maneka and Shreya extended protections further. The Court often acts as a defender of Article 19 against excessive limits, while still acknowledging the “reasonable restrictions” explicitly allowed in the Constitution.

Controversies and Debates: Reasonable Restrictions

By design, Article 19 rights are not absolute. Reasonable restrictions – e.g. for “public order,” “decency,” or national security – can justify laws that limit speech or assembly. But defining “reasonable” or “public order” has proven controversial. For instance, India’s sedition law (IPC 124A) is an offshoot of colonial rule and is hotly debated under Article 19.

In Kedar Nath Singh v. Bihar (1962), a five-judge bench upheld the sedition provisions but narrowly interpreted them: the Court said sedition can only be charged if the speech involves an “intention or tendency to create disorder, or disturbance of law and order; or incitement to violence.” In other words, mere criticizing the government is not sedition unless it incites unrest. This line – requiring actual incitement – has been reaffirmed (e.g. in Indra Das v. Assam, 2011) and protects ordinary dissent under Article 19.

Many observers view the sedition law itself as a relic that clashes with free speech. Mahatma Gandhi famously decried it as “the prince among the political sections of the IPC, designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen.” In recent years, critics have pointed out that sedition charges are sometimes used against journalists, activists or students – as if those opposing or insulting the government violate Article 19 – despite Kedar Nath’s strict test.

For example, in 2021 a Delhi court charged climate-activist Disha Ravi under sedition for sharing a farmers’ protest toolkit (accusing her of “inciting violence”), but the Supreme Court quickly ordered her release, noting no evidence of any violence. Such incidents fuel debate over whether the state is stretching “reasonable restrictions” too far.

Similar controversies arose over online speech. Section 66A of the IT Act, struck down in Shreya Singhal (2015), had criminalized sending “information that is grossly offensive, menacing, or causes annoyance.” Activists argued this was so vague it could capture normal criticism or satire, chilling expression. The Supreme Court agreed, invalidating 66A as unconstitutional under Article 19. The Shreya ruling underscored that restrictions must clearly fit one of Article 19(2)’s grounds; mere “annoyance” was not listed, so it was struck down. Even today, questions about internet censorship and “fake news” laws reflect the tension between security/order and free speech.

Other debates include the scope of “public order” versus the right to protest. Governments sometimes impose curfews or section-144 bans on assemblies, citing Article 19(3). When does maintaining order cross into stifling legitimate dissent? Similarly, laws on defamation or contempt of court permit restricting speech for personal reputation or judicial authority. Critics warn these can be misused to muzzle critics of politicians or sensitive reporting.

In short, the interplay between Article 19’s freedoms and its restrictions are an ongoing dialogue in India’s public life. Each controversy – whether over sedition, digital speech, assembly bans or other laws – forces courts and citizens to clarify where the line of “reasonable restriction” lies. So far, the courts have tended to read Article 19 generously, siding with free expression. As Justice Patanjali Shastri put it in Romesh Thappar, even if free speech “involves risks of abuse, [it is better] to leave a few of its noxious branches to their growth, than… to prune them away”.

In everyday India, these debates play out in stories: a journalist challenges a gag order, young activists question the sedition charges, students refuse forced slogans, or netizens defy internet shutdowns. Anecdotes like the 2012 arrest of two women for Facebook comments (which led to the test case Shreya Singhal or the routine drop in sedition convictions despite a surge in cases underscore that Article 19 remains deeply contested. Through it all, however, Article 19 endures as a living promise: that Indians enjoy the core liberties of speech, assembly and association. It has weathered amendments and crises, but thanks to landmark judgments and civic vigilance, it continues to anchor India’s democracy.

Conclusion: Article 19—The Living Heartbeat of Indian Democracy

Article 19 is more than just a set of legal provisions—it is the living, breathing soul of India’s democratic spirit. It empowers every citizen to speak, think, move, work, and assemble freely, making participation in the democratic process meaningful and robust. Over the years, despite political upheavals, emergency excesses, technological revolutions, and evolving social norms, Article 19 has remained resilient—constantly tested, debated, and redefined, yet never diminished in relevance.

Through landmark judgments, the judiciary has interpreted its freedoms broadly and its restrictions narrowly, often siding with individual liberty over authoritarian convenience. Whether it was the press censorship battles in the 1950s, the personal liberty crisis during the Emergency, or the online free speech challenges of the digital era—Article 19 has stood as a constitutional compass guiding India toward openness, accountability, and democratic maturity.

However, freedom is never automatic or absolute. The fine balance between liberty and responsibility, dissent and disorder, continues to challenge lawmakers, courts, and citizens alike. In a world of misinformation, polarization, and state surveillance, defending Article 19’s essence is not just the court’s job—it is a civic duty. Every protest, every tweet, every debate, and every petition is a reminder that the freedoms guaranteed by Article 19 must be exercised with vigilance, defended with courage, and passed on intact to future generations.

In the end, Article 19 is not just about rights—it’s about the right to be heard, to be different, and to belong in the ever-evolving narrative of the world’s largest democracy.

Share this article with your friends and family to keep them informed!

🔍 Explore More: https://thinkingthorough.com

📩 Let’s Connect: Have thoughts or suggestions? Drop us a message on our social media handles. We will be waiting to hear from you!!

Read about Article 21 of the Indian Constitution : https://thinkingthorough.com/article-21-a-living-right/

References

ARTICLE 19. (n.d.). FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS. https://law.uok.edu.in/Files/5ce6c765-c013-446c-b6ac-b9de496f8751/Custom/ARTICLE%2019.pdf

Article 19 of the Indian Constitution. (n.d.). https://samistilegal.in/article-19/#

Mahawar, S. (2024, May 3). Article 19 of the Indian Constitution – IPleaders. iPleaders. https://blog.ipleaders.in/article-19-indian-constitution/

The Constitution (Forty-Fourth Amendment) Act, 1978| National Portal of India. (n.d.). https://www.india.gov.in/my-government/constitution-india/amendments/constitution-india-forty-fourth-amendment-act-1978#:~:text=%28a%29%20in%20clause%20%281%29%2C

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Article 19 of Indian Constitution

What is Article 19 in one word?

Freedom.

What is the Article 19 Amendment?

Several amendments have modified Article 19. The First Amendment (1951) is most notable—it added more grounds for restricting free speech, like public order and incitement to offenses.

When was Article 19(f) removed?

Article 19(1)(f), which guaranteed the right to property, was removed by the 44th Amendment in 1978.