When we think of criminal trials, most of us imagine powerful eyewitnesses or dramatic confessions, thanks to how movies and TV shows portray the courtroom. These stories often make it seem like justice is only served when there’s clear, direct evidence. But in real life—especially under Indian law—many criminal cases are decided not by what is seen or heard firsthand, but by circumstantial evidence.

Circumstantial evidence may not point straight at the truth like direct evidence, but it often builds a strong chain of facts that can lead to a fair and logical conclusion. In fact, it plays a crucial role in Indian criminal trials, especially when direct evidence is missing or unreliable.

This article explores how circumstantial evidence works in our legal system, why it’s so important, and how the courts use it to uncover the truth. By understanding this, we can see how justice is often achieved not just through what is obvious, but through what can be reasonably and intelligently inferred.

What is Circumstantial Evidence? A Closer Look at Its Role in Criminal Trials

In the world of criminal law, not every case comes with a clear eyewitness or a smoking gun. This is where circumstantial evidence — also called indirect evidence — plays a powerful role. Unlike direct evidence, which straightforwardly proves a fact (like someone witnessing a crime happen), circumstantial evidence builds a story by connecting dots. It relies on inference — a logical process of drawing conclusions based on the facts surrounding the case.

Think of it as a puzzle. Each piece on its own may not reveal much, but when carefully assembled, they form a complete picture. Under Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, “evidence” includes both oral statements made by witnesses and documentary evidence, such as documents or electronic records. Circumstantial evidence fits into this framework as relevant and admissible, even if it’s not a direct observation of the crime itself.

Interestingly, this concept isn’t new — it dates back to Roman law, where indirect proof was crucial in uncovering the truth. A popular legal phrase sums up its essence:

“Men may tell lies, but circumstances do not.”

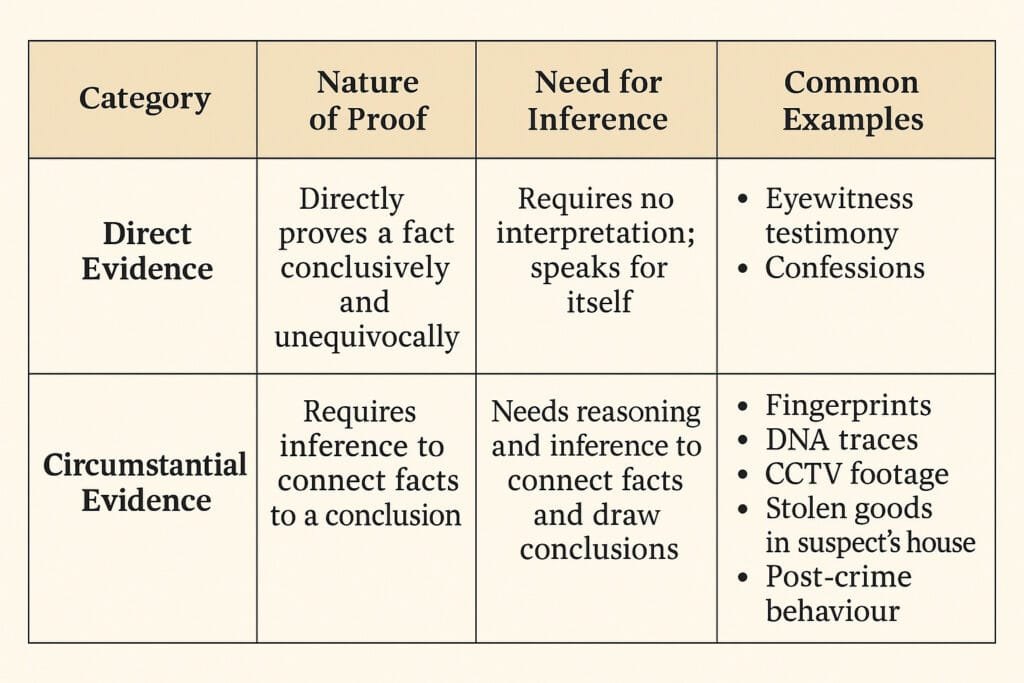

How is Circumstantial Evidence Different from Direct Evidence?

The key difference lies in inference.

- Direct evidence proves a fact without needing interpretation — for instance, a witness testifying that they saw the accused commit the crime.

- Circumstantial evidence, on the other hand, requires reasoning to reach a conclusion. It’s drawn from the context — the behaviour, surroundings, or consequences related to an event.

Here are some simple examples to make it clear:

Snowfall Analogy: If you watch snow fall, that’s direct evidence. But if you go to sleep with clear roads and wake up to a white blanket of snow, you infer it snowed — that’s circumstantial evidence.

Stolen Goods: If police find stolen items in someone’s house, it’s circumstantial. It suggests involvement but doesn’t directly prove the person stole them.

Post-Crime Spending: If a suspect goes on a shopping spree right after a theft, that behavior can be used as indirect evidence of their involvement.

Murder Scenario: Imagine hearing a commotion, then seeing someone leave a room covered in blood, holding a knife — and discovering a body inside. You didn’t see the murder, but the surrounding facts strongly suggest who did it.

Why Circumstantial Evidence is Crucial in Indian Criminal Trials

In many criminal cases, especially serious ones like murder, direct evidence is often missing — not because it doesn’t exist, but because most crimes are committed secretly. Criminals go to great lengths to avoid leaving any direct trail.

That’s where circumstantial evidence becomes a powerful tool in the justice system. It allows courts to build a strong, logical chain of events that points clearly to the accused. If the chain is unbroken and each link is solid, it can lead to conviction — even without a direct witness.

Courts have time and again emphasized that if circumstantial evidence leads to only one reasonable conclusion — that the accused committed the crime — it is enough to secure justice. When used carefully and correctly, it helps the legal system see through deception and reach the truth.

The Legal Framework of Circumstantial Evidence in India

When it comes to criminal trials in India, evidence is everything. But not all evidence is direct or straightforward—sometimes, it’s the indirect clues, the context, and the chain of connected facts that help the court arrive at the truth. This is where circumstantial evidence plays a vital role.

The Indian legal system, through the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (IEA), lays down a clear and structured framework to guide courts on what counts as admissible evidence—including both direct and circumstantial types. Let’s understand how Indian law treats evidence and how circumstantial elements become powerful tools in a courtroom.

What Does the Indian Evidence Act Say?

Section 3 of the IEA defines “evidence” broadly. It includes:

- Oral Evidence – Statements made by witnesses in court.

- Documentary Evidence – All documents, including electronic records, presented for the court’s inspection.

Besides these, even admissions or confessions made by the parties can be considered during the trial, depending on the context.

Relevancy of Facts: The Starting Point (Sections 5 to 11)

One of the most important concepts in the IEA is “relevancy”—only facts that are logically connected to the issue at hand can be admitted as evidence.

- Section 5: Only facts in issue and relevant facts are admissible. Circumstantial facts must be logically connected to the case to be considered.

- Section 6 (Doctrine of Res Gestae): Events or statements that are part of the same transaction can be admissible, even if not directly related to the crime.

- Section 7: Facts that are the occasion, cause, or effect of other facts (like a weapon found at the crime scene) are relevant.

- Section 8: This section brings motive, preparation, and conduct into the picture:

- Motive indicates why a person might commit a crime.

- Preparation includes acts like buying poison or weapons.

- Conduct—such as fleeing the scene—can reflect guilt or awareness.

Burden of Proof and the “Last Seen” Doctrine (Section 106)

Sometimes, certain facts are known only to the accused. Section 106 of the IEA says that if a fact is especially within a person’s knowledge, that person must explain it.

This is often used in the “last seen together” scenario: if the accused was last seen with the deceased and cannot explain what happened after, it creates a strong link in the prosecution’s chain. But courts are clear—this cannot replace the burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Circumstantial Evidence in the Digital Age (Section 65B)

With the rise of digital footprints, electronic records—like CCTV footage, mobile data, or chats—have become key circumstantial evidence. Section 65B of the IEA deals specifically with how such data can be admitted in court.

To be valid, these records must be backed by a proper certificate under Section 65B(4), proving their authenticity. The Supreme Court has made it clear: this certificate is not optional—it’s mandatory.

This section ensures that even in the age of smartphones and surveillance, our legal system keeps up with the times and allows technology to serve justice.

Admissibility and Limitations of Circumstantial Evidence in Indian Criminal Trials

Circumstantial evidence, by its very nature, is based on inference rather than direct observation. To prevent wrongful convictions based on indirect proof, Indian courts have set strict legal safeguards that must be met before such evidence can be relied upon. These standards ensure that the conviction is based on a solid and logical chain of events, not assumptions or guesswork.

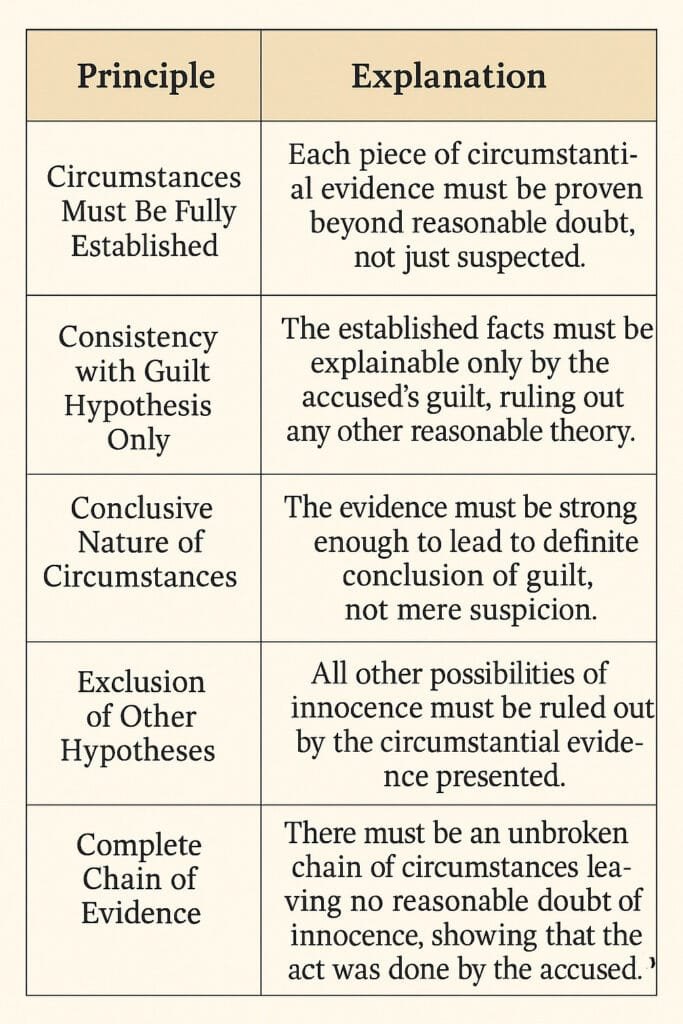

⚖️ The Five Golden Principles: Foundation of Fair Convictions

In the landmark judgment of Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra (1984), the Supreme Court of India laid down the “Five Golden Principles” (also called Panchsheel) for cases relying solely on circumstantial evidence. These principles act as a protective shield against miscarriage of justice:

- Every Circumstance Must Be Fully Established

Each fact the prosecution relies upon must be proved clearly and definitively—not merely suggested or speculated. Every link in the chain must be shown beyond reasonable doubt. - Facts Must Point Only to Guilt

The evidence must be consistent only with the guilt of the accused. If the facts can support any other reasonable explanation—like innocence—the case falls short. - Circumstances Must Be Conclusive

The chain of evidence should lead to one solid conclusion: that the accused is guilty. Suspicion or vague doubt is not enough. - Alternative Theories Must Be Ruled Out

The circumstances must rule out every other possible explanation, except that the accused committed the offence. If another reasonable hypothesis exists, the accused cannot be convicted. - Chain of Evidence Must Be Complete

The evidence must form an unbroken chain, leaving no room for alternative interpretation. The events must point so strongly toward the accused that, in all human probability, they alone could have committed the crime.

These principles are not just procedural rules—they reflect the Indian judiciary’s deep commitment to protecting individual liberty and preventing injustice, especially when relying on indirect forms of proof.

🔗 Importance of an “Unbroken Chain” and the “Beyond Reasonable Doubt” Standard

Indian courts consistently stress that circumstantial evidence must be so complete that it leads to one conclusion: the guilt of the accused. If even one link in the chain is missing or if there’s room for two different interpretations, the court is duty-bound to choose the one that favors the accused.

🔍 “Mere suspicion, no matter how strong, cannot take the place of legal proof.”

This standard ensures that convictions are based not on assumptions but on reliable, legally acceptable proof.

Need for Corroboration

Circumstantial evidence rarely works in isolation. To be effective, it must be supported by other facts that build a clear and cohesive narrative.

In Hanumant Govind Nargundkar v. State of M.P., the Supreme Court stressed that unreliable or uncorroborated evidence—especially from doubtful witnesses—cannot be the basis for conviction. Courts must be cautious when the evidence could have been fabricated or motivated by bias.

Motive: Helpful but Not Essential

Having a motive helps strengthen the prosecution’s case, but its absence does not automatically mean acquittal. However, in cases based only on circumstantial evidence, lack of clear motive can make the chain of events weaker, and the benefit of doubt may go to the accused.

📜 Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act: Clarified Limits

Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act allows the court to expect an explanation from the accused when certain facts are specifically within their knowledge. But the Supreme Court has made it clear: this section cannot replace the prosecution’s responsibility to prove the case. The burden of proof lies with the prosecution, and only when they’ve met that burden can the onus shift to the accused to explain further.

Judicial Scrutiny and Technological Evidence

Courts today not only examine testimonies but also evaluate forensic evidence, CCTV footage, digital data, and scientific reports to ensure that every piece of circumstantial evidence directly connects to the accused. This rigorous scrutiny adds an additional layer of legal protection for the accused, reinforcing the idea that innocent people should not be punished due to weak or speculative evidence.

Circumstantial Evidence in Modern Crime Solving: How Technology is Transforming Indian Criminal Trials

In today’s digital age, the role of circumstantial evidence in criminal trials has expanded far beyond traditional clues and observations. Modern crime-solving relies heavily on technology—DNA analysis, biometric records, CCTV footage, and digital footprints—all of which contribute to building strong, court-admissible chains of evidence, especially when direct witnesses are absent.

One of the most significant breakthroughs has been in forensic science. DNA profiling, fingerprint analysis, and biological samples like blood or saliva have become powerful tools in identifying offenders. DNA evidence, with its almost negligible error rate, has played a key role in serious cases like murder and sexual assault. Yet, despite its accuracy, Indian courts have traditionally viewed it as corroborative rather than standalone evidence, citing concerns over lab infrastructure and possible contamination. However, recent cases—like Abdul Nassar v. State of Kerala—show a shift, where DNA forms part of an “unbroken chain of circumstances” that leads to conviction.

Similarly, CCTV footage has emerged as one of the most reliable forms of circumstantial evidence. It captures real-time visuals that can establish the presence or actions of the accused—sometimes more convincingly than a human witness. Indian law now permits such electronic evidence under Section 65B of the Indian Evidence Act, provided proper certification is followed. Courts have also warned that failing to produce available footage can cast serious doubt on the prosecution’s case.

Another major development is the rise of digital evidence. From IP address logs and mobile GPS data to browser history and metadata, digital footprints have revolutionized investigations. These records help trace online activity, track movements, and even reveal deleted or hidden files. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) treats these digital records on par with paper documents, ensuring they’re legally recognized and protected from tampering through mandatory hashing procedures.

All of this is being reinforced by India’s New Criminal Laws, which now require forensic teams to visit crime scenes in serious offenses (those carrying 7+ years of punishment) and mandate videographic recording of evidence. These reforms reflect a growing trust in scientific and electronic evidence and aim to reduce reliance on weak eyewitness accounts or forced confessions.

In short, circumstantial evidence in India is no longer limited to fingerprints on a weapon or bloodstains on clothes. It now includes a wide array of technologically generated clues that can paint a full picture of the crime—accurate, objective, and harder to dispute. While this strengthens the criminal justice system, it also brings new challenges in maintaining data integrity and ensuring fair trials. As courts and law enforcement adapt to these changes, circumstantial evidence is set to become the backbone of modern criminal justice in India.

Landmark Judgments That Shaped Circumstantial Evidence Law in India

The role of circumstantial evidence in criminal trials has been significantly shaped by a series of landmark Supreme Court judgments in India. These judicial pronouncements not only define the legal standards required for conviction based on indirect evidence but also showcase the evolving nature of judicial scrutiny aimed at protecting the rights of the accused.

One of the most foundational rulings came in Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra (1984), where the Supreme Court laid down the iconic “Five Golden Principles” (Panchsheel) for evaluating circumstantial evidence. These include requirements that the circumstances must be fully established, exclude every possible hypothesis except guilt, and form a complete and unbroken chain that unerringly points to the accused. This case set the gold standard for courts to follow, ensuring that convictions are not based on assumptions or half-truths.

An earlier yet equally crucial case, Hanumant Govind Nargundkar v. State of M.P. (1952), emphasized that circumstantial evidence must leave no reasonable doubt. The Supreme Court overturned the conviction due to weak and uncorroborated testimony, reinforcing the need for credible, corroborated, and consistent evidence to sustain a conviction based solely on circumstantial facts.

More recently, in Abdul Nassar v. State of Kerala (2025), the apex court reaffirmed the importance of an unbroken chain of incriminating circumstances. In this high-profile rape and murder case, the Court upheld the conviction only after carefully analyzing evidence like DNA reports, suspicious conduct, the “last seen together” theory, and the recovery of key forensic materials—all forming a compelling chain linking the accused to the crime beyond reasonable doubt.

Another illustrative decision, Vaibhav v. State of Maharashtra (2022), highlighted the dangers of gaps and inconsistencies in the circumstantial chain. The Court reversed a murder conviction, ruling that the prosecution failed to eliminate alternative possibilities and did not establish motive or critical links. It emphasized that if two interpretations are possible, the one favoring the accused must prevail. Conviction was sustained only under Section 201 IPC for causing the disappearance of evidence.

Together, these judgments reflect a robust and evolving jurisprudence. From Hanumant to Sharad Sarda, and then to modern cases like Abdul Nassar and Vaibhav, the Supreme Court of India has consistently emphasized high standards for relying on circumstantial evidence in criminal law. By correcting lower court errors and reinforcing the “beyond reasonable doubt” and “complete chain” doctrines, these rulings safeguard against miscarriages of justice and ensure that circumstantial evidence is applied with utmost judicial care in Indian criminal trials.

Conclusion: A Powerful Pillar of Justice

Circumstantial evidence is not a weak or secondary form of proof—it is a powerful and essential part of the Indian criminal justice system. In cases where direct evidence is missing, circumstantial evidence helps courts piece together the truth through a logical and convincing chain of facts.

Indian courts treat such evidence with strict judicial scrutiny. The landmark case of Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra laid down the famous “Five Golden Principles”, which act as strong safeguards to prevent wrongful convictions. These principles ensure that every piece of circumstantial evidence forms an unbroken chain that leads only to one conclusion: the guilt of the accused—beyond all reasonable doubt.

With the rise of modern tools like forensic science, CCTV footage, and digital evidence, circumstantial evidence has become even more reliable and detailed. Today, technology plays a huge role in solving crimes, and Indian law is evolving to match this shift. The introduction of the New Criminal Laws reflects this change, showing that the legal system is ready to adapt while still maintaining high standards of proof.

In the end, the careful use of circumstantial evidence—supported by law, logic, and technology—shows India’s strong commitment to truth, justice, and public trust. It remains a crucial pillar that upholds the rule of law in a fair and effective way.

Share this article with your friends and family to keep them informed!

🔍 Explore More: https://thinkingthorough.com

📩 Let’s Connect: Have thoughts or suggestions? Drop us a message on our social media handles. We will be waiting to hear from you!!

References

CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE AND ITS EVIDENTIARY VALUE, accessed on July 11, 2025, https://www.thelegalwatch.in/post/circumstantial-evidence-and-its-evidentiary-value

Circumstantial Evidence – Drishti Judiciary, accessed on July 11, 2025, https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/to-the-point/bharatiya-sakshya-adhiniyam-&-indian-evidence-act/circumstantial-evidence

Reinforcing the Necessity of Corroboration in Circumstantial …, accessed on July 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/reinforcing-the-necessity-of-corroboration-in-circumstantial-evidence:-hanumant-govind-nargundkar-v.-state-of-m.p./view

Types of Evidence – YouTube, accessed on July 11, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8iJV6YoG134

Admissibility of circumstantial evidence and in subsequent proceedings – iPleaders, accessed on July 11, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/admissibility-of-circumstantial-evidence-and-admissibility-in-subsequent-proceedings/

Sharad Birdhi Chand Sarda vs State Of Maharashtra on 17 July, 1984 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1505859/

Five golden principles of case to be proved for placing a reliance on …, accessed on July 11, 2025, https://litigatinghand.com/five-golden-principles-of-case-to-be-proved-for-placing-a-reliance-on-the-circumstantial-evidence/

Case Law Hanumant Govind Nargundkar Vs.State of MP | PDF | Criminal Justice – Scribd, accessed on July 11, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/846221977/Case-Law-Hanumant-Govind-Nargundkar-Vs-State-of-MP